DRIVE DOWN Main St. in Allegany, N.Y., past strip malls and sandwich shops and a never-ending line of steel poles with Buffalo Bills flags dangling from them and you will eventually come upon a piece of local history. The Burton Hotel first opened its doors in the 1930s, a post-prohibition, no-frills bar and grill that suited the blue-collar locals it catered to. Students from nearby St. Bonaventure eventually adopted it, drawn in by the cheap beer in plastic cups and well-seasoned half-pound burgers, banding together each night to sing “Piano Man” after the bartenders announced last call. The relationship proved mutually beneficial: It was Bonnies alumni that saved the Burton in 2019, swooping in to buy the business just before it would have been forced to close. The place stopped operating as a hotel long ago, but its owners still rent out three apartments above the bar. Student-athletes occupy two of them. The world’s most famous NBA reporter lives in the other.

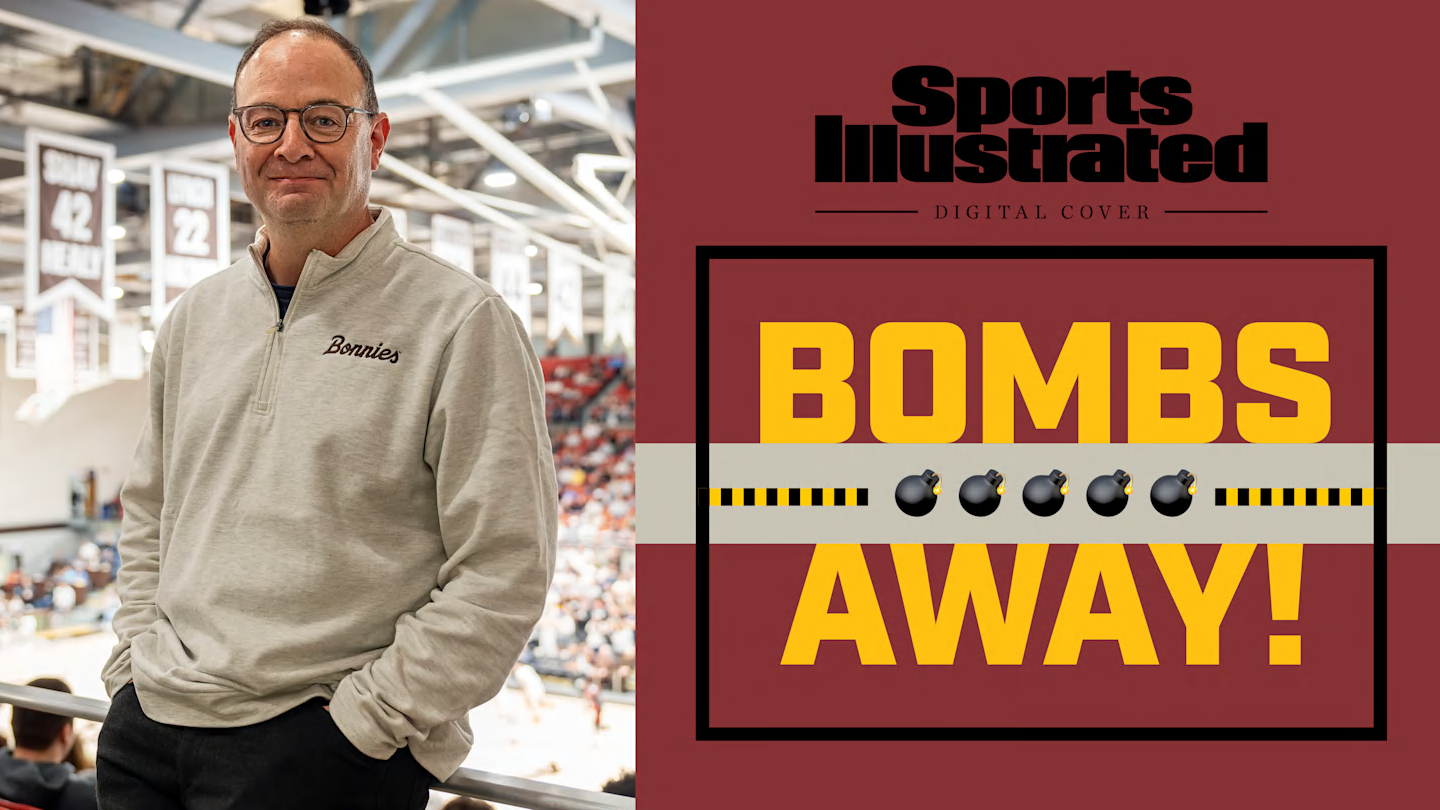

In September, Adrian Wojnarowski announced his retirement from media, abruptly walking away from ESPN (and a $7.3 million annual salary) to return to his alma mater, St. Bonaventure, in the newly created position of general manager of the men’s basketball program (and $75,000 a year). The New York Times covered it. So did CNN, Fox News and CNBC. On ESPN, the network’s remaining news breakers—Adam Schefter, Pete Thamel and Jeff Passan—hit the airwaves to pay tribute. On social media, millions of followers with alerts set for his posts—Woj bombs, as they became known—fired off some version of the same question: Why?

After all, this wasn’t a job. It was the job, the kind sports journalists spend a career working for. Wojnarowski—Woj for the purposes of brevity and character count—did. He sharpened his reporting chops in the ’90s covering Jerry Tarkanian’s dysfunctional Fresno State program for the Fresno Bee before spending a decade as a columnist with The Record in New Jersey. In 2007 he pivoted to the NBA beat, first with Yahoo Sports and later ESPN. He’s dined with Kobe Bryant, consulted with owners on coaching hires, done the walk-and-talk—the act of sidling up to a player during his trip from the locker room to his car or the team bus, a reporting technique that if Woj didn’t invent, he most certainly made trendy—more times than he can remember.

He revolutionized what it means to be a reporter, harnessing social media to disseminate breaking news to an audience with an insatiable appetite for it. What began as an experiment—“This is your new spot for Adrian Wojnarowski and Johnny Ludden’s breaking NBA news,” read Woj’s maiden tweet the day before the 2009 draft. (Ludden remains at Yahoo Sports, where he is the editor in chief.)—evolved into a platform with a Wembanyama-like reach.

This is your new spot for Adrian Wojnarowski and Johnny Ludden’s breaking NBA news on Yahoo! Sports.

— Adrian Wojnarowski (@wojespn) June 24, 2009

Consider: In August, representatives from Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign reached out. They had settled on their nominee for vice president and wanted Woj to break it. Alas, another outlet scooped him before he could.

So why quit? Some of it, Woj says, is easy to explain. There was no conspiracy. He wasn’t forced out. Wasn’t threatened with a pay cut. At 55, he was simply burned out. Insiders are the most well-compensated journalists. But the hours are brutal. Holidays, birthdays, barbecues—all threatened by the pursuit of a transaction. Last year, as a Philadelphia 76ers–Los Angeles Clippers deal involving James Harden came together, Woj decamped overnight in an airport because he was afraid the Wi-Fi on a cross-country flight wouldn’t work. Last summer, he ducked out of a family movie night to break news of Cleveland Cavaliers forward Evan Mobley’s contract extension. His wife, Amy, refers to his phone as a fifth family member. It goes to bed with you. It goes on vacation with you. It’s uninvited … but it’s everywhere you go.

He was ready to walk away. But he wasn’t ready to go away. Enter St. Bonaventure, the 166-year-old Franciscan college that sits on a plot of land in upstate New York, sandwiched between Olean and Allegany, 70-ish miles from Buffalo and a lot further from anything else. Notable alums include Hall of Fame center Bob Lanier, Fox anchor Neil Cavuto and Adrian Wojnarowski, class of ’91. Its basketball program has experienced waves of success, from the Lanier-led roster that contended for national titles in the late 1960s to the ’18 team that stunned UCLA to pick up its first NCAA tournament win since then.

For Woj, everything traces back to St. Bonaventure. He arrived on campus in 1987, lured north from his hometown of Bristol, Conn. He met Amy there, connecting over a shared love for basketball, journalism and The White Shadow. On their first date, they argued about the coaching effectiveness of Bobby Knight. He learned the craft in the student newsroom, churning out copy for The Bona Venture. Columnists carried the clout in those days, agenda setters like Harvey Araton, Mark Kriegel and Mike Lupica, and Woj aimed to be one of them. A roommate, ticketed for law school, once smirked that a sportswriter would never earn more than $50,000 a year. Fifty thousand a year, thought Woj. “Are you kidding?” he says. “I would have signed a 40-year contract.”

In 2021, the NCAA, after legislation in more than a dozen states opened the door for student-athletes to profit from their name, image and likeness, codified NIL in its rulebook, radically altering the college sports landscape. Collectives, effectively fundraising organizations, quickly formed. To navigate NIL, athletic departments began to staff up, creating new positions—including general manager.

Over the last year Woj spearheaded St. Bonaventure’s search for one. There were challenges. The pay was low and, unless you were an alumnus, living in a town frozen over three months a year wasn’t appealing, either. Last spring Woj began to think: Maybe I should do it. The NBA grind was getting to him. In March, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He was already doing most of the job—advising school officials, calling recruits, steering businesses to the Bonnies’ collective, Team Unfurl—so why not take it on full-time? “What I was doing, it just wasn’t fulfilling anymore,” Woj says. “I was just done. This is what gets me excited. To learn something new, to be part of something like this. It’s a whole new challenge.”

FULL DISCLOSURE: Adrian Wojnarowski is a friend. In 2016, Woj recruited me to join The Vertical at Yahoo Sports and a staff that included, among others, a young reporter named Shams Charania, who has now, by default, become the NBA beat’s preeminent bomber. A month before he announced his retirement, Woj was a guest at my wedding. My brother, Andy, even worked Woj into his best man’s speech. “Sources close to the situation say Chris vastly outkicked his coverage,” Andy said. From a back table, Woj confirmed it. There was a no phones rule at the reception. Only one attendee broke it. Woj’s reason: A player he had been monitoring was closing in on a two-way deal.

But quitting ESPN? Returning to St. Bonaventure? I didn’t know. Few did. Jay Wright was among the first to have an inkling. In 2022, weeks after leading Villanova to the Final Four, Wright resigned as the Wildcats’ coach. NIL was ramping up, the transfer portal was filling up and there was speculation Wright didn’t want any part of it. Last March, Woj called Wright and asked why he had quit. “Jay just said, ‘I felt like I wasn’t present with my family,’ ” Woj recalls. During his final season Wright jotted down notes to himself after tough losses. He stuffed them in a book, to be opened in case he ever had the urge to return.

Another resource: Bob Myers, the former Golden State Warriors GM. In 2023, after 11 years overseeing Golden State’s dynasty, Myers walked away. Woj was among those who counseled Myers during the decision. Myers was happy to do the same. When Woj told Myers he was thinking about leaving, Myers told him he should. “Bob’s brutally honest with you,” Woj says. “And he’s like, ‘You’re not going to be fun to be around if you do this another year.’ ” When Woj expressed reservations about walking away, Myers reminded him, “Quitting on top is not the same as quitting.”

Besides, Myers, who joined ESPN last year, could see what was happening. “He was not enjoying each day, each ‘win’ he was getting in the industry,” Myers says. During draft week in June, Woj waved over Myers in a hotel lobby. Myers asked how he was doing. As he spoke, Myers noticed tears welling up in Woj’s eyes. “He looked at me and he said, ‘I don’t think I can do this anymore,’ ” Myers recalls. “And I just said, ‘You shouldn’t.’ Because really, what’s it for? I think he felt like the cost to continue to do it was too much.”

There was a line in Woj’s retirement statement: Time isn’t in endless supply. “That was about the cancer,” he says. Last February, Wojnarowski went in for a physical. Blood tests revealed an elevated PSA, or prostate-specific antigen. His doctor sent him for an MRI. Nothing showed up. He took another PSA test. Still high. This time the doctor recommended a biopsy, which in March revealed early-stage cancer. He learned the news minutes before a remote appearance on NBA Countdown. Head foggy, he did the hit.

The prognosis, Woj says, is good. “When you hear cancer, you think about it going through your body like Pac-Man,” Woj says. “Prostate cancer, it generally stays confined to your prostate and is typically slow growing.” He has no symptoms and says the cancer is “pretty limited in scope.” Active surveillance is the current treatment, which translates to quarterly checkups and regular monitoring. He’s been instructed to improve his eating habits, exercise more and get better sleep. Surgery is still a possibility, but for now doctors say the only reason to have it is if he can’t mentally deal with having the cancer inside him.

Cancer didn’t force him out, Woj insists. But it did bring some clarity. “I didn’t want to spend one more day of my life waiting on someone’s MRI or hitting an agent at 1 a.m. about an ankle sprain,” he says. In May, Woj traveled to Rogers, Ark., for a memorial for Chris Mortensen, the longtime NFL insider who died in March from throat cancer. Mortensen spent more than three decades at ESPN. When Woj arrived in Bristol in 2017, Mortensen was among the first to welcome him. Many ESPNers made the trip to Arkansas. What Woj was struck by was how many did not. “It made me remember that the job isn’t everything,” Woj says. “In the end it’s just going to be your family and close friends. And it’s also, like, nobody gives a s—. Nobody remembers (breaking stories) in the end. It’s just vapor.”

On Sept. 18, Wojnarowski made it official. He called ESPN chairman Jimmy Pitaro. Pitaro, who was aware of the cancer diagnosis, asked Woj if he was sure. ESPN did, after all, owe him $20 million over the final three years of his contract. “Jimmy was great,” Woj says. “But the only reason to stay was the money. That wasn’t a good enough reason.” Pitaro asked if Woj would consider staying on in a different role. But going back to writing the sharp, biting columns he did for years at Yahoo didn’t interest him. Pitaro suggested he could return to Countdown for the playoffs. “Our audience deserved somebody who’s fully immersed in the NBA every single day and I would not be,” Woj says. “In my mind, I didn’t have value to them anymore.”

Besides, he knew what his family wanted. Amy was ready for him to go. Years earlier, when Woj disappeared into his phone to report a big story—a DeMarcus Cousins injury, Woj recalls—she asked when she would be one. His kids, Annie and Ben, were ready, too. Just before the NBA draft, Woj called Ben. He was leaning toward quitting and wanted to get his son’s take on it. Ben was blunt. “People think your job is great,” Ben said. “I think your job f—ing sucks. Retire—and go travel with Mom.”

WOJ HAS a question. It’s early November and he has just ducked out of his office in the Reilly Center, St. Bonaventure’s 5,480-seat arena. Woj works from a cold concrete room with an air conditioner embedded in the window so old he swears Lanier once fidgeted with it. He is seated at the head of a conference table in a meeting room on campus. To his left is Bob Baratta, a partner at MiCamp, a processing solutions provider. To his right, a pair of officials from Ashley Furniture, a retailer with ties to the area. After a few minutes of small talk, Woj fixes his gaze on the Ashley employees. “Let me ask you this,” he says. “Are you having a more positive experience in the processing world or in logistics?”

Officially, a college GM has wide-ranging responsibilities. Transfer portal management, messaging, alumni relations, at least according to the Bonnies’ job listing. When Woj informed St. Bonaventure athletic director Bob Beretta of his interest, Beretta was thrilled. “I knew he’d make an incredible asset,” Beretta says. He asked Beretta to run it by the team’s coach, Mark Schmidt. “No brainer,” Schmidt says. “Best portal recruit we’ve ever had.” Per university rules, though, the position had to be posted publicly. And Woj had to formally apply. “Haven’t done a resume since my newspaper days,” Woj says. “At least they didn’t ask for my GPA.”

In the NBA, the GM calls the shots. In college, it’s reversed. “This is Coach Schmidt’s program,” Woj says. “I’m fitting into his culture.” And raising money. Lots of money. St. Bonaventure’s enrollment—some 2,000 undergrads, “roughly the size of most high schools,” says Woj—is among the smallest in Division I. Alums are generous but there are only so many to call on—Woj himself has donated seven figures to the university—and so many times you can. “We’re not going to have the money the top dogs in our league have,” Schmidt says. “But we need to stay in the ballpark. If we can, we can sell our program. And sell Woj.”

The focus, Woj says, is on sustainable revenue. Baratta, an old neighbor of Woj’s, has met with several local businesses. If he convinces them to work with him, the Bonnies’ collective gets a piece of the revenue. The trucking business offers similar opportunities. In October, Team Unfurl cut a deal with Quiiiz, an online trivia game, that will rake in six figures. Woj sits in on each meeting, not to offer any specific insight but to let them know the program—and Woj—will be part of the deal. At the end of the meeting with Ashley Furniture, Woj reminded the reps he would be happy to make an appearance at a nearby store.

The transfer portal has become college basketball’s free agency. In 2024, more than 1,000 men’s players entered it. Woj keeps thick (digital) files on players likely to land there. Major-program players averaging 10 to 12 minutes per game. International players, junior college, Division II. He’s cultivating relationships with NIL agents, just as he did in the NBA. If St. Bonaventure misses on a guy the first time around, his job is to be ready if they get a second crack.

Ready with money, and with opportunity, St. Bonaventure can’t go dollar for dollar with most schools. But Woj’s presence, the Bonnies hope, can close the gap. His deep network of NBA coaches, agents and front office executives offers players a bridge to the next level. “Those are relationships that I couldn’t build or we couldn’t build as a staff in the next 30 years,” Schmidt says. “He’s going to be able to help us get in the door with guys because of who he is and the trust he has built over his career.”

Indeed, NBA executives who used to feed Woj information are now advising him. On navigating a salary cap. On building out a staff. On creating a player-friendly environment. In the Reilly Center, the team has built out a room for immediate family to gather before and after games. He cut a deal with iSlides to provide players with personalized sandals. He’s worked with the video team to create hype videos, borrowing from the Toronto Raptors’ “We the North” campaign in hopes of deepening the program’s ties to the Toronto area, which is home to several former Bonnies players. Through camps and open practices, Woj wants to “plant our flag” in that hotbed of basketball talent.

IN SEPTEMBER, days after he announced his ESPN exit, Woj’s phone buzzed. A trade between the New York Knicks and the Minnesota Timberwolves was cooking and someone involved wanted to know if Woj wanted any intel on it. Woj’s response: Congratulations. But I don’t give a s—. A few days later, Karl-Anthony Towns was headed to New York. Woj was headed to his office.

St. Bonaventure is a new chapter in Woj’s career. He’s not sure if it’s his last. He knows he won’t work in media again. He’s not interested in climbing the NBA ladder, either. G League, pro scout—forget it. Friends from other schools—Dusty May, the Michigan men’s basketball coach and Lindsay Gottlieb, the women’s coach at USC—have gauged his interest in their GM jobs only to be rebuffed. “There’s nowhere else on the planet I would work this hard for,” Woj says. “I can’t say I won’t do something else someday. But nothing like this.”

Financially, he’s fine. He’s grateful for the $75,000 salary, even if it represents a 99% pay cut from his ESPN gig. “Honestly,” he says, “I thought it would be $50,000.” He doesn’t know what he would have done had the Bonnies’ job not been available. “I probably would have done another season,” Woj says. “But it would have been a mistake.” He’s made millions in his career, but he hasn’t spent them. He still lives in the same house in New Jersey that he bought shortly after returning to work for The Record. Annie, 25, is an Emerson film school graduate working in New York. Ben, 22, is in his last year at the University of Denver. It’s $1,500 a month to rent the apartment above the Burton, and he and Amy have had no issues with the baseball players living next door. “We’ve been really lucky,” Woj says. “We have enough.”

Recently, after a quick dinner at Perkins (“I can eat off the 55-plus menu”) Woj returned to the office. It was late, after 10 p.m., but two players were out on the floor. One had a student manager rebounding for him. The other was alone. Woj was reminded of something Clippers president Lawrence Frank told him: Everybody’s job is everybody’s job. He dropped his bag and started shagging balls. “We’re here to serve these guys,” Woj says. “That’s the job.” A job that feels a lot different.