Engaging active mobility

The landscape of Chinese online translingual practice is characterized by a robust orientation towards lifestyle. Internet users traverse the boundaries between the global and local spheres, giving rise to new lifestyles that are from other cultures. One notable example is the translingual term “city walk,” which has emerged as one of the most popular hashtags on Chinese social media platforms. Accompanying it are translingual terms related to urban transportation, such as “city ride” and “city climb”, which have also gained widespread acceptance in China.

Take “city walk” as an example. While the idea originated in the United Kingdom, its translingual introduction by Chinese netizens has swiftly popularized it and, more significantly, put it into tangible action. During the first half of 2023, the combined views of “city walk” on prominent Chinese social platforms like Weibo and Xiaohongshu surpassed one billion, marking a staggering year-on-year search volume increase of 190.93%. Notably, on Xiaohongshu (Fig. 1), data from August 2023 indicates a 700% surge in the number of “city walk”-related posts over the past three months, with total interactions increasing by more than 600% (Zhang 2023). On Weibo, the hashtag #citywalk# has garnered 220 million views (Fig. 2). The overwhelming presence of topics related to city walking among millions of netizens has turned the term into a heated meme on Weibo. As illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2, many cities, scenic spots, historical resorts, and cultural programs leverage the hashtag to attract enthusiasts and potential tourists alike. The translingual introduction of the concept has sparked widespread interest in trendy means of urban travel across China. This online discourse has translated into tangible action, with city walking gaining momentum among residents and tourists nationwide. The discursive dissemination of city walk-related topics and the growing popularity of this new urban transportation mode mutually reinforce each other.

Topics related to city walk on Xiaohongshu.

Topics related to city walk on Weibo.

As an advanced form of “city walk”, “city ride” has also gained significant traction across social media platforms, with the hashtag #cityride garnering over 10 million views on Xiaohongshu and reaching a readership of 605,000 on Weibo (Fig. 3). Although bicycles held a long-standing tradition in China, after entering the 21st century, the dominance of bicycles as a primary commuting tool began to wane with the rise of cars and electric scooters. Over the past couple of years, cycling culture has experienced a resurgence, transforming into a fashionable sport and lifestyle choice. “City ride” was particularly evident in 2023. According to the “2023 Outdoor Living Trend Report”, the number of cycling-associated notes posted reached over 1.8 million in the year, an increase of nearly 400% compared to the previous year, with a total of more than 1.3 billion views (Xiaohongshu 2023). The report suggests that “city ride” is seen as a physical activity and a tool for emotional and mental health. Moreover, according to the “China Health Management White Paper” published in 2022, there has been a noticeable drop in residents’ satisfaction with their health. The data indicates that 80% of them started focusing on scientific exercise post-pandemic. This increased health consciousness has indirectly driven the trend of cycling. Cycling is often associated with a lifestyle symbol, a vehicle of self-regulation, or indicating a free-spirited personality. The popularity of “city ride” on Chinese social media platforms indicates that cycling has evolved into a popular form of exercise and a trendy leisure activity among the younger generation in China.

Topics related to city ride on Weibo.

Most posts under the topics attached to “city walk” and “city ride” show Weibo bloggers or vloggers’ unique travel experiences in the city with photos of local history, heritage, street art, humanities, architecture, and other urban subcultures based on their interests and preferences. The rapid spread of these active, urban transportation ways provides an alternative to address problems with urban mobility. If we situate the “city walk” and “city ride” heat in the urban landscape of China, we can find it aligns with the prevailing conditions in most Chinese cities. The heat epitomizes a societal pivot toward addressing urban environmental challenges and fostering a culture of sustainable and health-oriented living that has transcended borders to influence the traveling styles of Chinese netizens and the urban life of modern Chinese people. It well responds to China’s rapid urbanization that has happened in the past decades as the progress of its modernization but is accompanied by severe pollution problems on account of the increasing car ownership of urban families and the resulting changes in haze exposure levels (Wang et al. 2021). Since the 2008 Olympic Games, the Chinese government has prioritized environmental concerns, and the online community has played a crucial role in raising awareness about issues such as smog and the adverse health effects of fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5. The escalation of concerns about air quality has led to heated online discussions where translation serves as a discursive tool, which involves translating information about the causes and effects of smog, sharing data on air quality, and conveying the concerns and frustrations of the public both domestically and globally (Yuan 2020). The discursive translingual spreading of the eco-friendlier way of mobility is also one such endeavor. In China’s dense urban areas, where the dependence on automobiles contributes significantly to pollution, new ways of urban mobility such as city walking and riding emerge as a beacon of change, signaling a broader cultural shift to embrace more eco-friendly and health-aware transportation habits. Urban mobility is intricately tied to the climate crisis, with vehicle emissions serving as a significant urban pollution source, particularly in cities lacking traffic management strategies. Recent studies (e.g., Poli 2011) highlight that promoting active mobility and minimizing the necessity for travel presents the most comprehensive solution. Promoting active mobility, such as walking and cycling, responds to the pressing need to enhance physical activity levels, thus combating obesity and its impacts on health. Meanwhile, it also serves as a lifestyle-driven approach to prompt citizens to alter their transportation habits, favoring public transit and active mobility (Caimotto and Raus 2023: 149–151). Many official blogs such as “人民日报(People’s Daily)” (Fig. 4), “湖南电视台(Hunan TV)” (Fig. 5) and “央视新闻(CCTV News: China Central Television News)” (Fig. 6) promote Chinese tourism and local cultural programs by referring to the #citywalk# hashtag, encouraging residents and tourists to have a deeper exploration of the city and uncover its hidden charm and stories. The above cases show that the more eco-friendlier trend of mobility has been welcomed and integrated into daily life choices by Chinese people through its viral spreading on social media.

Official media post on city walk.

Official media post on city walk.

Official media post on city walk.

The viral dissemination of the translingual terms “city walk” and “city ride” on Chinese social media encapsulates a deliberate response of Chinese netizens, among whom most are young people, to the challenges of urban pollution and increasingly sedentary lifestyles. Such prevailing trends not only highlight society’s recognition of the need for change in urban mobility but also emphasize Chinese netizens’ commitment to addressing environmental and health-related concerns by embracing alternative modes of transportation and advocating for pedestrian-friendly urban lives.

Encouraging sustainable practice

Climate change has increasingly dominated media coverage since the beginning of the 21st century, highlighting the growing interconnection between environmental preservation and lifestyle choices. The anthropogenic environmental crisis stems from the high-energy-consuming lifestyles led by the expanding global population, where individual identities are constructed through lifestyle and consumption patterns. Rather than scrutinizing an economic system that perpetuates ceaseless growth and the depletion of finite energy resources, environmental protection has often been framed as a matter of individual decisions, which is propagated through the promotion of “green” and “sustainable” products and services (Caimotto and Raus 2023: 124–126). Such a shift in lifestyle is exemplified by the redefined concept of “stooping” among young people, departing from its traditional meaning of “bending downward.” The revised practice aligns with efforts to combat climate change and promote sustainability. Now, “stooping” refers to the act of salvaging discarded furniture and other items from the streets for reuse, as popularized by the New York-based Instagram account @stoopingnyc in 2019. This movement has garnered global traction among young individuals residing in unfurnished rentals, giving rise to a distinctive “stooping culture” on social media that fosters community and sustainability.

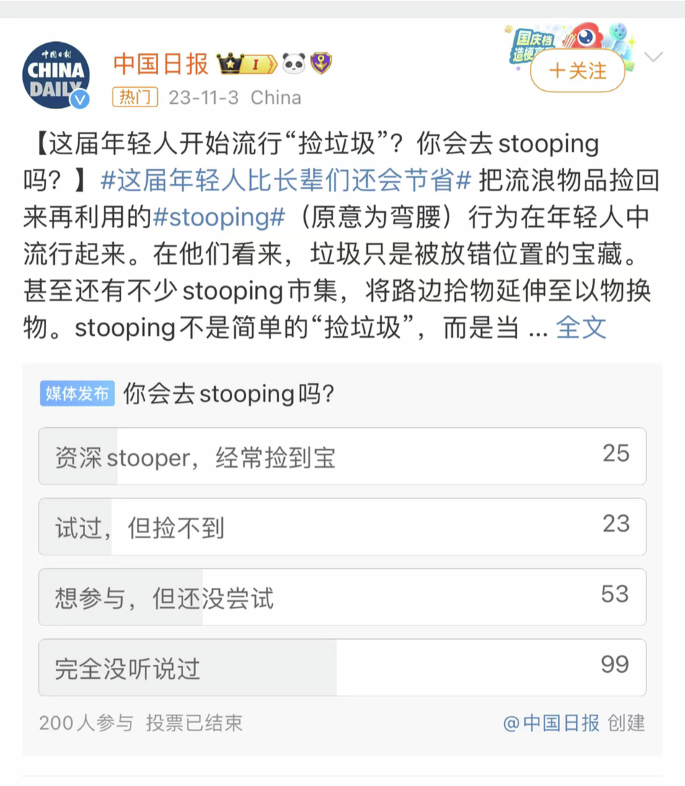

The concept of “stooping” initially spread to Chinese social media from Xiaohongshu, a platform with approximately 72% of its users born after 1990. Digital marketer Mikiko Chen, aged 27, was among the first in China to adopt “stooping.” Chen was inspired by New Yorkers who frequently left unwanted items on their doorsteps (“stoops”), and she was among the pioneers who used the hashtag #stooping on China’s Xiaohongshu platform. Subsequently, numerous stooping accounts emerged on the platform, each representing a city, with stooping-related posts garnering millions of views. As of the end of 2023, the hashtag #stooping on Xiaohongshu had accumulated over 8.13 million views and more than 6600 posts as retrieved on December 30, 2023, primarily advocated for by young people who champion new lifestyle politics. Additionally, on Weibo, a platform with nearly 80% of post-90s users, the practice of stooping has garnered attention, attracting more than one million views (Fig. 7). These trends indicate that young Chinese netizens have used translanguaging to express their embrace of this new global approach to environmental protection in daily life.

Topics and posts related to stooping on Weibo.

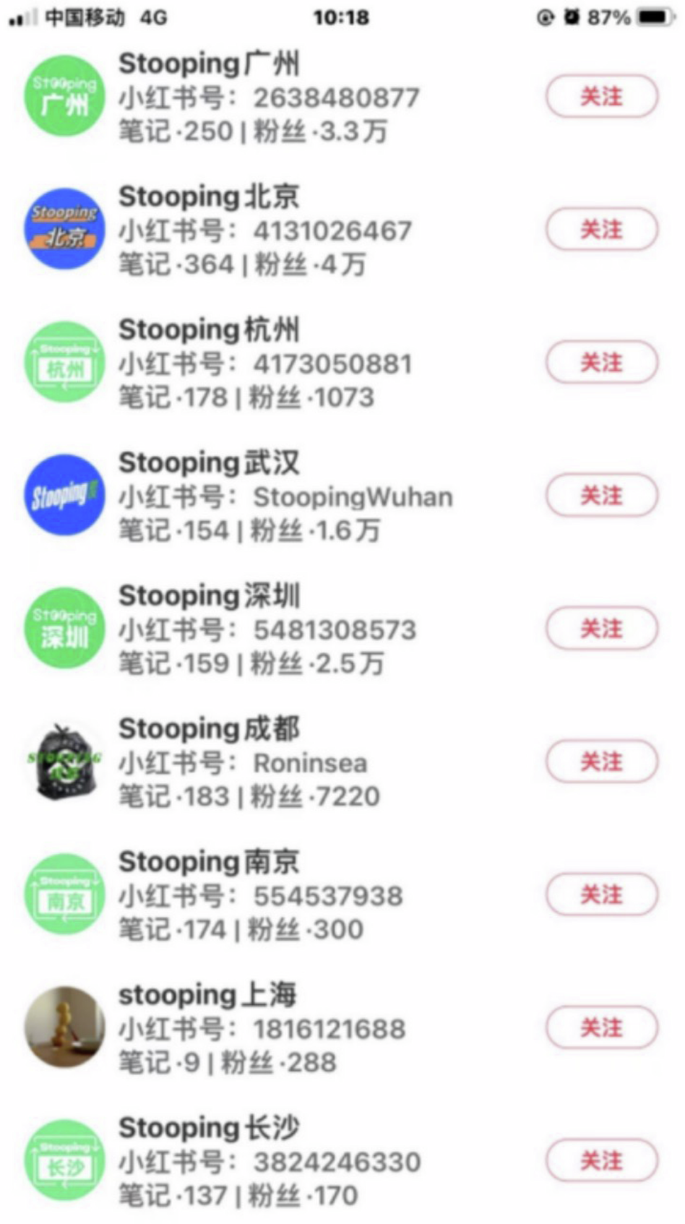

As depicted in Fig. 8, online communities have emerged across Chinese cities, such as “stooping 广州(Guangzhou),” “stooping 北京(Beijing),” and “stooping 武汉(Wuhan),” following the introduction of the term to China through translational practices. Moreover, the trend has gained popularity in major metropolises like Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, and Wuhan. Many “stooping” corners were established and shown on Xiaohongshu and Weibo, with many stooping activities documented. Like New York, these cities experience high tenant turnover and the abandonment of furniture, resulting in significant waste due to large migrant populations and advancements in production technology leading to surplus products. However, this surplus has resulted in the neglect and disposal of older items, contributing to resource waste and environmental issues.

Topics and posts related to stooping on Xiaohongshu.

Another popular translingual term on Chinese social media closely related to the trend of sustainable practices is “plogging”. “Plogging” originated in Sweden in 2016, and it is a compound of “plocka” (pick) and “jogga” (jog) in Swedish. “Plogging” combines sports(jogging) and environmental protection (picking up litter). It was highly supported and favored by environmentalists and fitness enthusiasts and spread from Sweden to other countries. On Xiaohongshu, #plogging has up to 900,000 views, and many online communities call for “plogging” events (Fig. 9). On Weibo, related topics have up to 8 million views, indicating the popularity of “plogging” on social media (Fig. 10).

Topics and posts related to plogging on Xiaohongshu.

Topics and posts related to plogging on Weibo.

Stooping and plogging are both signs of the Chinese collective awareness of environmental protection, sustainable development and social responsibility. The “2022 China Ecological Environment Status Bulletin” from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment emphasizes the urgency of addressing these challenges. The report highlights data indicating that 5.0% of the national land area is affected by acid rain, and soil erosion spans 2,653,400 square kilometers. Stooping and plogging introduced to China through online translingual practice arise as a practical and effective approach aligned with low-carbon environmental protection consumption principles. They emphasize a fluid item circulation process. By recycling and extending the lifespan of old items, they reduce waste, safeguard the environment, and foster community engagement and resource sharing. To some extent, the popularity of such practices is helpful for China to fulfil its commitment to achieving a “carbon peak” by 2030 and “carbon neutrality” by 2060. The eco-friendly stooping and plogging activities, advocated and spread through online discourse, offer alternatives to contemporary China’s environmental problems. It is probably for this reason that the official media “中国日报(China Daily)” also joins in to spread these ideas, as seen in Fig. 11.

Official media post related to stooping on Weibo.

The rise of the translingual term “roomtour” on Chinese social media also reveals concern over sustainability and the use of living space. Originating on YouTube, “roomtour” is a popular vlog genre globally, involving the sharing of videos showcasing personal living spaces and reflecting the owner’s taste, design philosophy, and approach to life. By the end of 2023, posts related to “roomtour” on Chinese Weibo exceeded 90,000, with the hashtag #roomtour# generating 200 million views. On Xiaohongshu, #roomtour# has over 90,000 notes and 130 million views(Fig. 12). Most of them are young immigrant residents in cities. Unlike the pursuit of large living places, young vloggers usually use the “roomtour” hashtag to produce new lifestyles that challenge traditional norms and established means of living and consumption.

Topics and posts related to roomtour on Weibo and Xiaohongshu.

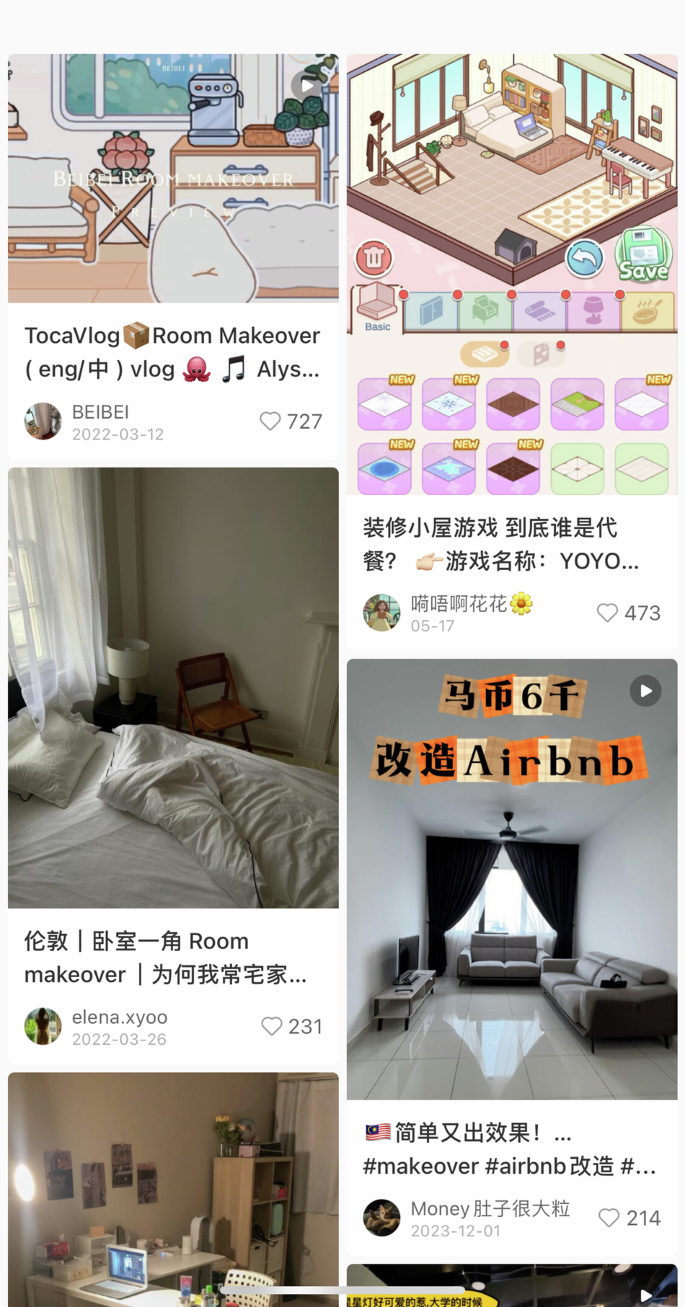

Noteworthily, one subgenre gaining traction within the room tour niche is “room makeover” videos (Fig. 13). Chinese vloggers showcase the transformation of living spaces using creative decoration and repurposing of existing items, promoting resourcefulness and a budget-conscious approach to design. This trend has increased interest in second-hand transactions and fostered a community that values environmental responsibility and sustainable living. Within the new middle class, there is a noticeable consumption stratification—28% embody a “spend as you wish” mentality, while 35% adopt a “save where you can” philosophy (Ocean Engine, 2020), highlighting the nuanced spending behaviors within this group. The growing environmental consciousness has also led to a broader embrace of sustainable consumption practices, epitomized by the “Recycle, Reduce, Reuse” movement. Quest Mobile (2023) indicates that 46.8% of the active users on platforms for trading second-hand goods come from the new middle class, with those born after the 1990s driving the boom in second-hand consumption. The social media trend of #roomtour not only promotes individuality and creativity but also champions sustainable living.

Topics and posts related to room makeover on Xiaohongshu.

The second-hand market in China has seen substantial growth, particularly among the youth, who increasingly rely on second-hand platforms to deal with their idle belongings. This trend is steadily growing. According to a 2021 report by Frost & Sullivan and Tsinghua University Institute of Energy, Environment and Economics, along with Zhuanzhuan Group, China’s second-hand consumption market surpassed one trillion yuan in 2020, and it is anticipated that transactions of idle items in China will exceed three trillion yuan by 2025 (Frost and Sullivan 2021). This signifies that the second-hand trade has become a stylish and sustainable lifestyle choice, reflective of a low-carbon, environmentally friendly approach to living. The shift among young consumers away from traditional “single-use” consumption toward more sustainable practices indicates a broader change in behavior that encompasses environmental awareness, economic considerations, and the desire for unique personal experiences.

The translingual terms such “stooping”, “plogging”, “room tour” and “room makeover” represent more than just a trend—they signify a cultural and social shift in consumer behavior towards personalized, creative, and sustainable lifestyles among the younger generation in China. As these trends continue to evolve, they are poised to further influence the lifestyles and values of the broader consumer base in the country. They exemplify how online communities are taking proactive measures to embody social responsibility and showcase their dedication to sustainable practices, actively contributing to the country’s green transformation. In their pursuit of sustainable living, they are cultivating a culture of conservation and sustainability that extends beyond personal habits, influencing broader societal norms and behaviors.

Creating new clothing and dining styles

China’s socio-historical backgrounds have wielded significant influence over clothing styles. Post-1949, simplicity and monotony characterized fashion, with deep blue and dark green being prevalent colors, reflecting the socio-political ethos of the time, which was marked by a focus on practicality, equality, and the suppression of individualism in favor of collectivist ideals. However, in the 1990s, Western fashion culture began to make its mark, leading to the widespread adoption of suits for formal events and the embrace of casual wear typified by jeans and T-shirts. This shift mirrors the changing societal and cultural dynamics in Chinese clothing style, as the traditional simplicity and monotony of clothing gave way to a more diverse and individualistic approach to fashion. The rise of global economic and communication systems has amplified the importance of personal identity, granting individuals greater autonomy in expressing diverse identities through consumption and lifestyle preferences (Caimotto and Raus 2023: 124–126), thus paving the way for sartorial expressions.

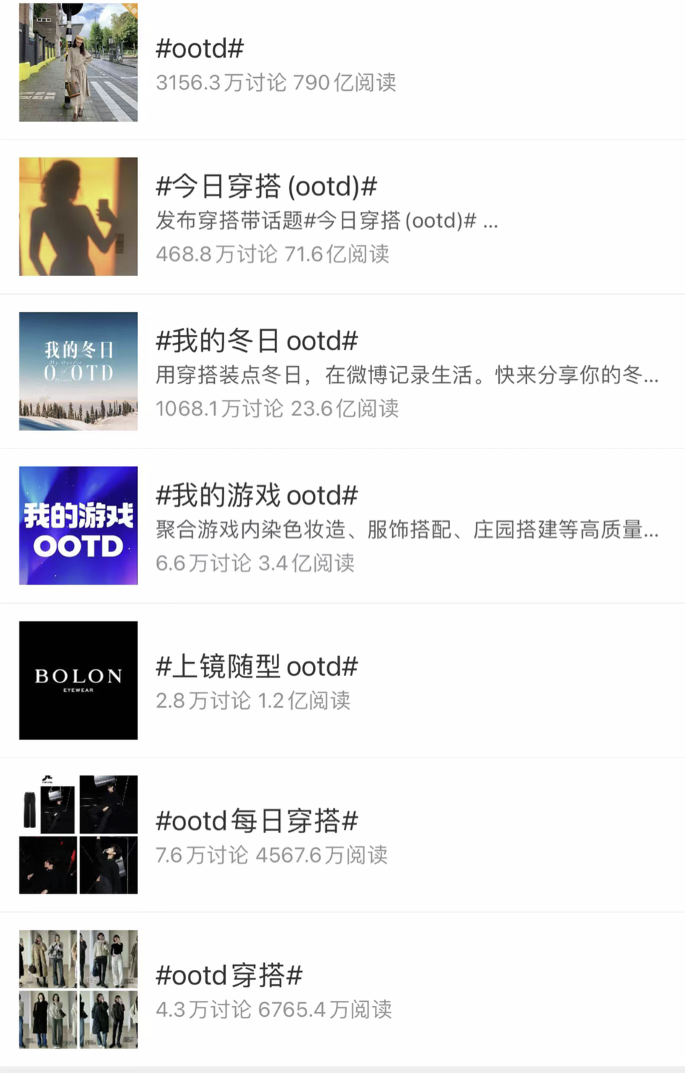

In recent years, the diversification of clothing choices for Chinese people is increasingly evident, serving as a testament to the burgeoning pluralism in personal style. The advent and proliferation of social media and e-commerce platforms have further fueled the spread of fashion trends and facilitated purchasing behaviors. These digital avenues have also enabled translingual practices in fashion, offering consumers exposure to a myriad of styles and trends. For instance, the translingual term “OOTD” has widely appeared on Chinese social media platforms. By the end of 2023, the hashtag #ootd# on Weibo garnered 79 billion reads and 31.563 million discussions (Fig. 14); and on Xiaohongshu, it amassed 3.17 billion views. As shown in Fig. 15, Chinese netizens, primarily girls, share their fashion choices and showcase their style online. More importantly, the translingual hashtag #ootd# enables them to connect with like-minded people and gain visibility within the online community and even in the fashion industry.

Topics and posts related to OOTD on Weibo.

Topics and posts related to OOTD on Xiaohongshu.

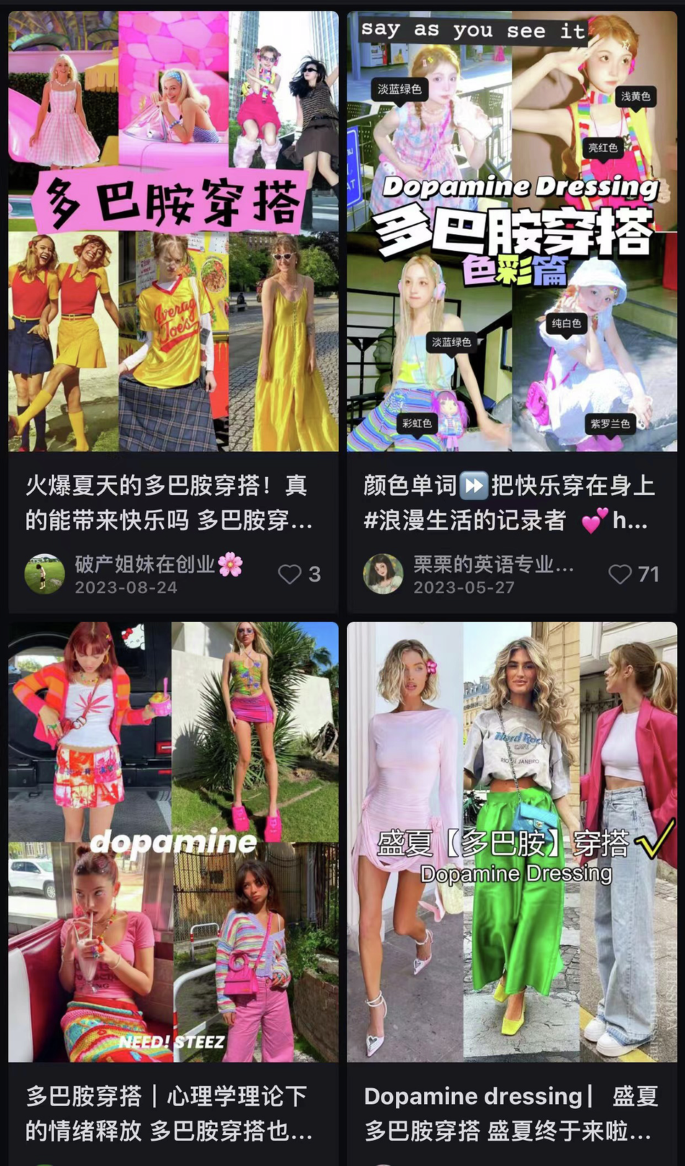

Additionally, the translated meme “多巴胺穿搭 (dopamine dressing)” emerged as a prevailing fashion trend on Chinese social media platforms in 2023. The translated term #多巴胺穿搭# has also sparked a frenzy across Chinese social networks, with over 930,000 related posts on Xiaohongshu and nearly 500 million views (Fig. 16). On Weibo, there are 104,000 discussions and 290 million views for the same hashtag (Fig. 17). Featured by vibrant hues such as bright yellow, berry red, lime green, and pink purple, dopamine dressing defies traditional color principles, focusing on mood enhancement and emotional well-being. This trend, introduced by fashion psychologist Dr. Dawnn Karen, triggers the release of dopamine, known as “happy hormones,” promoting positivity through clothing choices. The trend’s popularity on social media platforms like Xiaohongshu and Weibo reflects a broader societal embrace of vibrant colors, personal inner values and inclusive fashion narratives. In the pictures and videos dubbed dopamine dressing, Chinese girls demonstrate loose clothing, shirt, and pant combinations, which alleviate body image anxiety often associated with the “body-shaping” style, offering a broader definition of beauty that transcends traditional concepts of body type in the Chinese culture. In this way, “Dopamine Dressing” resists traditional bodily and gender constraints, granting online communities the freedom to express their beauty. It achieves this by promoting gender-neutral attire, age-inclusive styles, and body-positive designs that prioritize personal expression. For instance, unisex clothing breaks down gender barriers by allowing any gender to wear the same piece, while bright colors and comfortable cuts for various body types are embraced across age groups. These elements of “Dopamine Dressing” challenge the conventional norms of what is considered appropriate for specific genders, ages, and body shapes, thereby transcending concerns of gender, age, and body image. This approach not only enriches the Chinese public aesthetics but also fosters a new identity among the younger generation, known as the “Dopamine Girl/Boy”.

Posts and topics related to Dopamine Dressing/多巴胺穿搭 on Xiaohongshu.

Posts and topics related to Dopamine Dressing/多巴胺穿搭 on Weibo.

The rise of translingual terms like “OOTD” and “多巴胺穿搭” signifies a shift towards placing greater importance on clothing choices and a rebellion against traditional social norms. These terms signify a widening diversity and freedom in clothing choices, encouraging individuals to embrace their uniqueness and creativity. Clothing fashion is a complex system that generates fashion phenomena and practices, reflecting lifestyles and ideologies. By challenging conventional beauty standards and promoting body positivity, the newly emerging clothing styles underpinning the above translingual terms contribute to a more inclusive and open-minded fashion ideology that gradually gains public acceptance and resonates within communities.

People always develop new dietary habits in the changing environment. The relationship between food and people’s health, identity, and social class has evolved significantly, particularly in the 20th century, with industrial food production and new agricultural techniques, which granted access to unprecedented food quantities, leading to changes in traditional diets and eating habits. However, the development of the food industry also brought forth new challenges, including health issues due to unhealthy eating habits and global hunger disparities. The impact of excessive meat consumption on climate change has also become a pressing concern. Some environmentalists and scholars suggest that addressing these challenges is feasible through increased consumption of fruits and vegetables. Recognizing this, the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization have spearheaded the initiative of promoting fruit and vegetables for health, environment and the future of mankind (Caimotto and Raus 2023: 170-172).

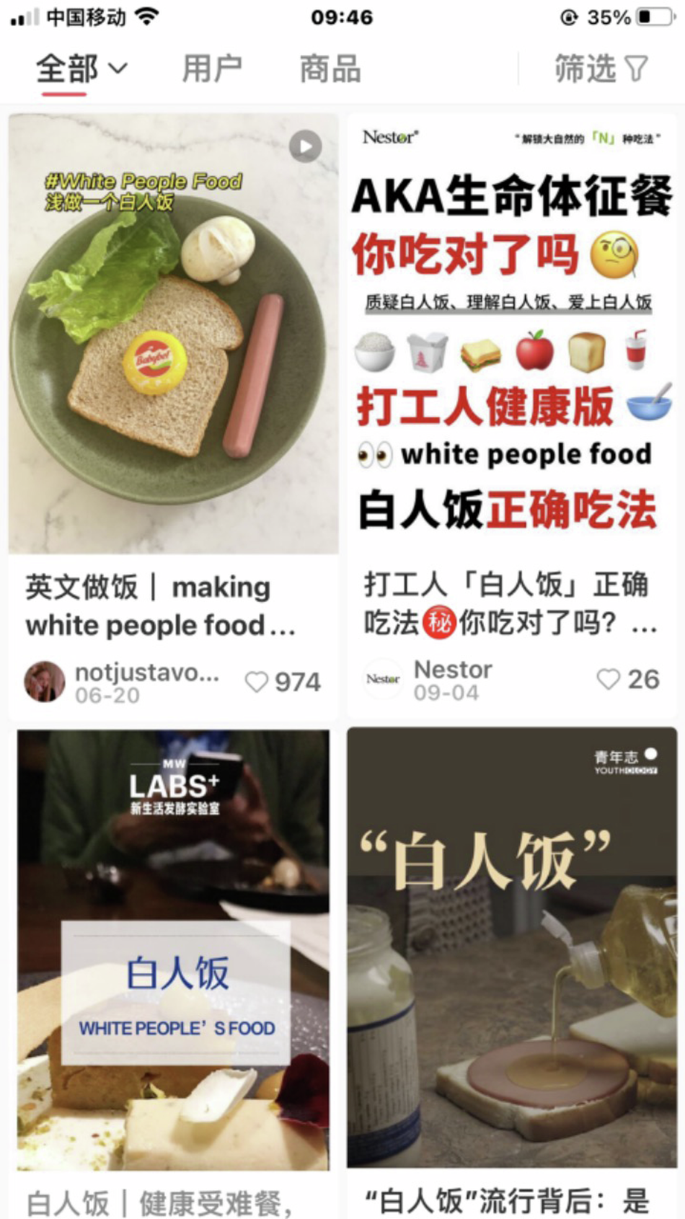

In 2023, China’s Internet has been buzzing with a new trend— white people food (白人饭). Since May 2023, many netizens have posted photos and videos of simple Western-style meals on social media platforms in China with the hashtag #white people food#. Interestingly, the term “white people food” was believed to be first put forward by Chinese international students studying overseas, who found themselves puzzled by the simple, cold lunches their Western classmates consumed—a stark contrast to the warm, varied, and traditionally cooked Chinese meals they were accustomed to. These lunches sometimes consisted of plain vegetables, like green beans, carrots, baby spinach, and celery, or other items like slices of bread and boiled eggs. Many social media users have promoted the health benefits of the simple white people lunch (Touma 2023). As the trend spread to China, Chinese netizens started sharing their experiences with these minimalistic meals, making #white people food# one of the hottest phrases on various platforms and local media. As of the end of 2023, the hashtag #white people food# on Xiaohongshu has surpassed 19 million views and garnered over 50,000 notes (Fig. 18). Furthermore, content related to #white people food# has attracted 6.345 million views on Weibo (Fig. 19) and official media such as “新周刊(New Weekly) ” also joined in the discussion of the food culture (Fig. 20).

Topics and posts related to white people food on Xiaohongshu.

Topics and posts related to white people food on Weibo.

Official media post related to white people food.

The elusive creation and dissemination process of the translingual term “white people food” best reveals the language hybridity and diversity in online translingual practice. Although it may have originated from the Chinese language, it takes the form of an English term, as shown in Figs. 18 and 20 and therefore is understood by many as a foreign concept. Because of its lower caloric density, the concept gained traction as a healthier dietary option to address issues of overnutrition and associated metabolic diseases on Chinese social media. The shift is particularly notable in contrast to an earlier era, specifically before China’s economic rise, when the dietary focus was on securing sufficient protein, fat, and sugar (Yan 2013). Nowadays, with basic nutritional needs largely met, the emphasis has shifted to incorporating vegetables like green beans, carrots, baby spinach, and celery. These vegetables are not only low in calories but also rich in dietary fiber, which is commonly lacking in contemporary diets. The popularity of “white people food” drives younger Chinese generations to adopt more balanced and nutrient-dense eating patterns, often associated with health and wellness, reflecting a broader acceptance and acknowledgment of nutritional benefits of other cultures. The online translingual practice has facilitated the rapid sharing of healthy lifestyles among countries, leading to increased awareness and changes in Chinese traditional diets and eating habits.