Journalist and author Hervé Kempf founded Reporterre as a print-media outlet dedicated to environmental issues in the late 1980s. He has worked with various media outlets, including Courrier International and Le Monde. He is the author of several books, including How the Rich Are Destroying the Earth (Green Books, 2008), translated into 10 languages, the comic book version of which (Comment les riches ravagent la planète, Seuil, 2024) was made in collaboration with cartoonist Juan Mendez. The book unpacks the relationship between structural social inequalities and the climate crisis.

Reporterre – “the media of ecology” – is a model of success, not only in terms of content, but also in business terms. The site is entirely free to access, and 98% of its revenue comes from reader donations (mainly small donations, says Kempf), while the remaining 2% comes from book sales, thanks to a partnership with Le Seuil publishing house. Managed by an association, the site has 2 million monthly readers and an annual budget of around €2.7 million. Reporterre currently has 27 permanent employees, including 19 journalists.

Reporterre has a very clearly defined editorial line: “We believe that the question of ecology is the key political issue of the early 21st century. Ecology is political, and cannot be reduced to questions of nature and pollution – even if we follow these vital issues closely. Ecology is about our common destiny, the future, and its situation is largely determined by social relations: it is therefore a political and social ecology that Reporterre presents and discusses.”

Voxeurop: Reporterre was first created in 1989. What prompted you to launch this project?

Hervé Kempf: In 1986 the Chernobyl nuclear disaster happened. It hit me hard. I started thinking about how the environment was so important, but there were no non-activist newspapers dedicated to the subject. I set about creating a newspaper with money I had inherited. But I knew this wasn’t enough. You need a lot of cash. Time, which was a very big paper at the time, decreed in January 1989, at the time of our launch, that the man of the year would in fact be the Planet of the Year, Planet Earth. The media and the people had realised that the environment was important. We got off to a good start. We sold an average of 26,000 copies every month, and ended up with 4,600 paying subscribers. The problem was that we were severely undercapitalised, and painfully short of cash. After a year, we had to stop. Time went by, and I became a journalist with lots of different media outlets before being hired by Le Monde in 1998 to cover the environment.

Interesting article?

It was made possible by Voxeurop’s community. High-quality reporting and translation comes at a cost. To continue producing independent journalism, we need your support.

Subscribe or Donate

Reporterre was relaunched in 2007. How did that happen?

In 2007, I wrote “Comment les riches détruisent la planète” (How the Rich are Destroying the Earth, 2008). The book explained the link between the social question and the ecological question, and the extent to which they are inseparable. To show how this was not just theoretical, but could be read through the daily news, I created a website, which I called Reporterre, and that was its second birth.

During those years, still at Le Monde, I kept the site going as a hobby, learning how to write for the Internet and getting to grips with it as a tool. Then, in 2012-2013, when Le Monde censured me and there was a dispute, I, along with some friends, took Reporterre to the professional level, aiming to turn it into a real news site, for which people would be paid to produce content.

(Read more about why Kempf left Le Monde, in his own words).

The advantage of the Internet is that it costs much less money than printing and distributing a printed newspaper. In 2013, Reporterre had no employees, just my free labour. Then, little by little, donations started coming in, and I was also giving talks on my book and asking people to pay not for me, but for the website. We started to get small grants from private foundations. I was soon able to start paying a few freelancers and create a fixed-term contract for a journalist. Traffic increased and so did donations, and a virtuous circle was immediately set in motion.

Your book – How the Rich are Destroying the Earth- has been translated into ten languages. Its comic book version, published in collaboration with the cartoonist Juan Mendez, explores the relationship between the structural social inequalities of our societies and the climate crisis. Why this book?

How the Rich are Destroying the Earth was a success, quickly selling 30,000 copies. It has now sold 70,000, and it’s still selling – we’re on to the fourth edition.

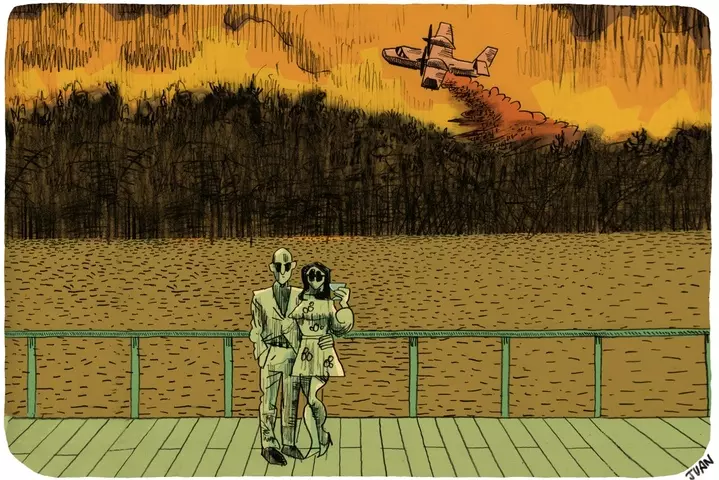

“You’re going too fast, Hervé!!”

An extract from Kempf/Mendez: Comment les riches ravagent la planète (Seuil, 2024).

The book had a major impact on the understanding of how the ecological question and the social question are indissoluble. At the time – I’m simplifying here – the left still saw the environment as a secondary issue, and environmentalists ignored or underestimated the challenge of inequality. There was a real need to articulate the relationship between the two issues. Now I’m delighted that it’s become commonplace.

What remains important to explain today is that the issue of the rich and inequality is not just about Musk and the ultra-rich. The issue involves all of Europe’s middle classes, if you look at the global income scale. Between 40% and 60% of people – including me, for example – in European countries are in the top 10% of the world’s richest. So it’s not a question of “bash the rich”. It’s about reducing inequalities across the board, by working together, in the rich countries, towards greater sobriety.

“Your drawing is not bad, but I’d had the 1% in red…”

“Sigh”

An extract from Kempf/Mendez: Comment les riches ravagent la planète (Seuil, 2024).

Reporterre has what you might call a “strong” editorial line. Would you say there is a link between political engagement and being a journalist?

Well, they are two completely different things. A journalist is someone who wants to relate the world to his or her contemporaries. And he or she will do so with the greatest possible honesty, by investigating, witnessing, checking the facts and looking for contradictions.

Afterwards, a certain attitude is made explicit: “I look at the world, but I don’t pretend to be objective. I look at it from a certain point of view”. This point of view is the editorial line.

Most journalists and media outlets do not clearly define their editorial line. At Reporterre, we define it by saying that the ecological issue is the key political issue of the 21st century. That’s the basis on which we try to tell the story of what’s happening.

To make this clear, I’ll take the example of The Economist, which is an excellent newspaper, and which has had a clear editorial line since its inception: it considers liberalism a mode of organisation that allows society to be harmonious, peaceful, prosperous, etc. From this point of view, they tell the story of the world. And they generally do it very well. But we know where they’re coming from.

What’s the difference between this and political engagement? Political engagement is when I assume a vision of the world and identify with a particular political doctrine or political party, and from then on I influence society by spreading the ideas of that party or doctrine and trying to convince people. With this comes the idea of assuming power.

As journalists, we don’t want to assume power, and if the greens do things that don’t suit us, we say so. We write very few opinion pieces, and I write very few editorials. We do news: we have an editorial line, a way of looking at the world, and we take it on board. That’s also called an angle in journalism.

And then there’s the question of independence. How do you ensure it?

This is a fundamental issue that guarantees the quality of the information: Reporterre is independent. We are run by a not-for-profit association. There are no shareholders. 98 percent of our income comes from readers. And it all comes from small donations. There are no big donors who would give €10,000 or even €5,000.

Does journalism have a specific responsibility in the current democratic crisis?

Journalism is not homogenous. The responsibility of journalists lies in not having fought when billionaires wanted to buy their media, in not having fought hard enough for their independence. So journalists have a huge responsibility.

We ask them to respect the fundamental principles of journalism. For me, the first of these is freedom. I would add this to the definition of journalism: to be a journalist is to be free and to work for freedom. You have to be free. It is the journalist’s freedom that guarantees the quality of the information he or she produces.

I tell the story of the world, and maybe I do it poorly, but you know what position I’m coming from, and you know that nobody is forcing me to tell you what I tell you. This is the responsibility of journalists: the fight for their own freedom and the fight for freedom in general. The price we should pay for the privilege of doing such a fascinating job is to fight for freedom. For our own freedom, and by extension for that of society as a whole.

There is also a structural impasse due to the crisis in the press.

It’s an economic system, yes. But there are courageous people, like Catherine André at Voxeurop, we at Reporterre, our colleagues at Arrêt sur Image and Mediapart… and all the young journalists who are fighting to create independent media. The independent press is growing. It may prove to be a source of inspiration for journalists in outlets that are enslaved to capital. We face constant economic change. But we must continue to fight for our independence from shareholders.

‘This is the responsibility of journalists: the fight for their own freedom and the fight for freedom in general’

Reporterre has a somewhat horizontal operational model that is not often found in the media. How does it work?

There’s a board of directors who steer the whole thing and make sure that it’s independent and that it respects the focus on information about ecology. I’m the editorial director, with a deputy. There is a general manager. And we’ve organised a “rotating editorial team”: every fortnight, one of the five or six most experienced journalists takes it in turns to edit the paper on a daily basis, chair editorial meetings, decide on the front page, etc. It’s an original system, which works very well, and helps us to develop a culture of collective intelligence.

In the beginning, Reporterre was very small, so I did everything myself. And then, little by little, we grew. I changed too, because I came from a very vertical world, Le Monde. We have a much more horizontal way of working, even if verticality is still sometimes necessary to resolve potential hesitancy.

The European context remains important. What does Europe mean to you today?

I remain attached to the idea of Europe. All the more so at a time when there is a rise in the far right – not to say fascism – which wants the break-up of Europe and, in the process, the reconstitution of communities that are separate from each other, with a fantastical vision of Europe that is racist and closed to the outside world.

I’m from the east of France, and I’m all too aware of the abominations that took place during the First and Second World Wars, but the European ideal, particularly for France and Germany, is to manage to live together while disagreeing and being different, but at the same time being at peace and working together. And we need this more than ever, given all the temptations of fragmentation, nationalism, withdrawal…

I know it’s an ideal, but we act according to an ideal. At Reporterre, we also work towards the ideal of an ecological, fair and, if possible, happy world!

The problem is that Europe remains within the logic of neoliberalism. There is the spirit of Europe, and then there is its political translation, which is extremely disappointing.

🤝 This article is published within the Come Together collaborative project