In brief

Experts caution defense attorneys on social media campaigns

Debate on ethics of “seeding” jury pools in high-profile cases

Panel discusses risks of public interviews during trial

Case illustrates privilege and disparities in the justice system

For the better part of a week after a Norfolk County jury found Karen Read not guilty of causing the death of her boyfriend, Boston police officer John O’Keefe, the case remained a fascination of the national news media.

On June 24, the “Today” show interviewed the foreperson of the jury, while ABC News touted an “exclusive” with five prosecution witnesses. Special prosecutor Hank Brennan “breaking his silence” about the jury’s verdict gained plenty of attention, as did the return volley from defense attorney Alan Jackson, which suggested that Brennan had violated his ethical duty by questioning the jury’s decision.

O’Keefe died on the snowy morning of Jan. 29, 2022, after a night out drinking with Read and other friends, including fellow officers. After leaving a bar, Read drove O’Keefe to the Canton home of fellow Boston police officer Brian Albert and claimed to have watched him enter the house, though multiple witnesses say he never made it inside.

Through two trials, the prosecution’s theory was that Read had struck O’Keefe with her SUV, breaking her taillight in the process, and he subsequently died in the snow. However, the defense alleged that something else happened to O’Keefe, perhaps a fight inside the home and/or an attack by the family dog. The seeds for the defense’s theories were first planted on social media, led by blogger Aidan Kearney, who uses the name Turtleboy. Kearney continues to face witness intimidation charges related to his advocacy in the Read case, though in May, Superior Court Judge Michael Doolin dismissed six of the 16 counts Kearney was facing.

Read’s first trial on charges of second-degree murder, manslaughter while operating under the influence of alcohol, and leaving the scene of personal injury and death spanned nearly two months, with opening statements on April 29, 2024, and closing arguments on June 25.

A key moment in the first trial was the revelation that State Trooper Michael Proctor had sent inappropriate text messages about Read while taking part in the investigation of O’Keefe’s death.

After five days of deliberations, Superior Court Judge Beverly Cannone declared a mistrial after jurors reported that they were “deeply divided.” Defense attorneys subsequently learned that the jury had been unanimous on acquitting Read of the most serious charge against her, second-degree murder, as well as on the leaving-the-scene charge, but they were unsuccessful in their bid to get those charges dismissed on that basis.

Jury selection in Read’s second trial began on April 1, with opening statements coming three weeks later. More than 40 witnesses would testify over 30 days in Read’s retrial.

Jurors got the case on Friday, June 13, and deliberated through the following Monday and Tuesday without reaching a verdict, at one point sending Cannone a list of four questions, including whether they would be considered a hung jury if they found Read not guilty on two charges but could not agree on the third.

Finally, on June 18, the verdict came. Read was found guilty only of operating a vehicle under the influence, for which she received the customary sentence of one year’s probation.

Beyond the prurient interest in theories about what happened outside — and perhaps inside — Albert’s home in the early morning hours of Jan. 29, 2022, there may be lessons for practitioners from the two Read trials, a panel of criminal law experts says.

Our panelists are:

Former Superior Court and Boston Municipal Court Judge John T. Lu, who now works as an independent mediator and teaches at Boston College Law School

Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers President Shira M. Diner, a lecturer and clinical instructor in the Defender Clinic at Boston University School of Law and a former public defender

Michael Kendall, founding partner of the Boston office of White & Case and a former assistant U.S. attorney; represented John Wilson in the Varsity Blues criminal trial, succeeding in getting all of the fraud and bribery counts against Wilson reversed on appeal and having the court order the government to return $1 million in forfeiture funds

Daniel S. Medwed, a criminal law professor at Northeastern University School of Law, who focuses his research and pro bono activities around the topic of wrongful convictions

Boston criminal defense attorney Benjamin Urbelis, who last year argued a case before the Supreme Judicial Court that established precedent requiring clerk-magistrates to provide defendants with notice and an opportunity to be heard before opening show-cause hearings to the public

Their responses to questions from Lawyers Weekly, edited for length, follow.

***

Q. Considering how Karen Read’s two trials played out, should defense attorneys now more strongly consider mounting a social media campaign to fund the defense and “seed” the jury pool in the appropriate case? Why or why not?

LU: The system as a whole — judges, prosecutors and defense counsel — need to rise to the occasion in dealing with the unusual case in which social media is a factor. Possible measures include focused social media questions on jury questionnaires related to YouTube, X, TikTok and other sites, as well as questions about interest in “true crime,” who potential jurors follow on social media platforms, and the use of fake name or moniker social media accounts by potential jurors.

True sequestration in hotels, bans on cellphones in the jury room at any time, and supervised use at other times during real sequestration, and written orders to jurors, signed and agreed to by the jurors, may be employed.

But the problem is deeper than can be addressed by these measures. A prominent pro-Karen Read blogger posted on X that as jurors entered the courtroom, he made unmistakable eye contact with a few of the jurors, suggesting that they knew who he was and that they knew he would be happy with the verdict they were about to return.

Attorneys should use caution in participating in social media campaigns to fund the defense or to “seed” the jury pool, even though it is obvious that this is what happened in the Karen Read case. You do not want to be the test case.

Every attorney involved in a high-publicity case should read Massachusetts Rule of Professional Conduct 3.6 and draw their own conclusions whether their participation in such a campaign would materially prejudice the trial or whether countervailing considerations — such as countering undue prejudice from publicity initiated by others — justifies the social media campaign.

An additional caution is in order. Social media is such a Wild West that an attorney might get involved with content providers with the best of intentions but then become entangled in illegal or unethical actions of content providers that unexpectedly intimidate witnesses, pressure witnesses, and defame innocent individuals. Always remember that legal consequences for actions may come years after the event.

Attorneys should use comprehensive client engagement letters in every case (and) include in those letters warnings to make private all social media accounts, to not accept friend requests except from people you know, not to post about the case, and that otherwise innocent posts might be distorted in court and used as a tool to pressure and harass you.

KENDALL: Purposely seeding the jury pool raises serious ethical issues. Prosecutors do it all the time with talking indictments and lurid allegations in court filings. Look at the massive, inaccurate publicity from the Varsity Blues case.

But that does not mean a judge will allow defense lawyers to respond in kind. We need to maintain the trust of the trial judge, the jurors, and the appeals court. A television audience does not acquit your client. Defendants can certainly raise funds necessary to try and offset unlimited prosecution resources.

Q. Do the Karen Read trials speak to the value of using a “kitchen sink” defense? Why or why not?

MEDWED: Not necessarily, because the second trial seemed tighter and more targeted than the first in that it emphasized reasonable doubt and did not fully develop the third-party culprit angle, even within the constraints imposed by the judge.

In essence, the strategy seemed rather straightforward: Insufficient evidence of the car having struck him plus flaws in the police investigation equaled reasonable doubt.

LU: They do, and they suggest that the time-honored kitchen sink defense retains its value. Ms. Read “won” her case based on a kitchen sink defense, despite defense counsel giving a fairly detailed opening. It may still be wise to limit the detail in an opening in a kitchen sink defense to avoid getting “boxed in” by the prosecutor based on your opening.

Also, let’s be cautious not to learn too much from this trial. Remember, Ms. Read had a potent Bowden shoddy investigation defense that may have overwhelmed everything else the prosecution did, particularly when driven by “true crime” enthusiasts on the jury.

Q. The defense obviously derived great benefit from prying into State Trooper Michael Proctor’s devices. Will clients expect defense attorneys to do this in every case? How should lawyers manage that expectation and the costs and potential benefits of seeking that information?

URBELIS: The defense didn’t pry into Michael Proctor’s devices. Rather, the FBI did. The FBI obtained Michael Proctor’s phone through a grand jury subpoena during the course of their investigation, and later both the defense and prosecution in Karen Read’s case got access to all of that content.

This was a very unique situation, obviously, and defense attorneys won’t now be expecting to routinely get extractions from the personal cellphones of investigating officers. It would take very specific, known information to articulate what information helpful to the defense is likely contained on such phones, rather than going on a “fishing expedition,” which isn’t enough reason for a court order.

In cases where this does come into play, though, it could be a goldmine for the defense, as we saw in Karen Read’s case.

KENDALL: Every defense team has to assume it must do its own investigation and actively gather evidence. Some prosecutors purposely slalom around exculpatory evidence and avoid gathering it to limit Brady disclosures. Defense lawyers need to routinely use Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 17(c) subpoenas to build their cases. There is great case law supporting this in the District of Massachusetts.

I have won numerous cases because of brilliant work from a private investigator I routinely use.

LU: Yes, clients will expect (this), and defense counsel should attempt to get into devices, including personal devices. Now is the time to do so because this window will close as police and law enforcement catch on that their electronic communications are fair game.

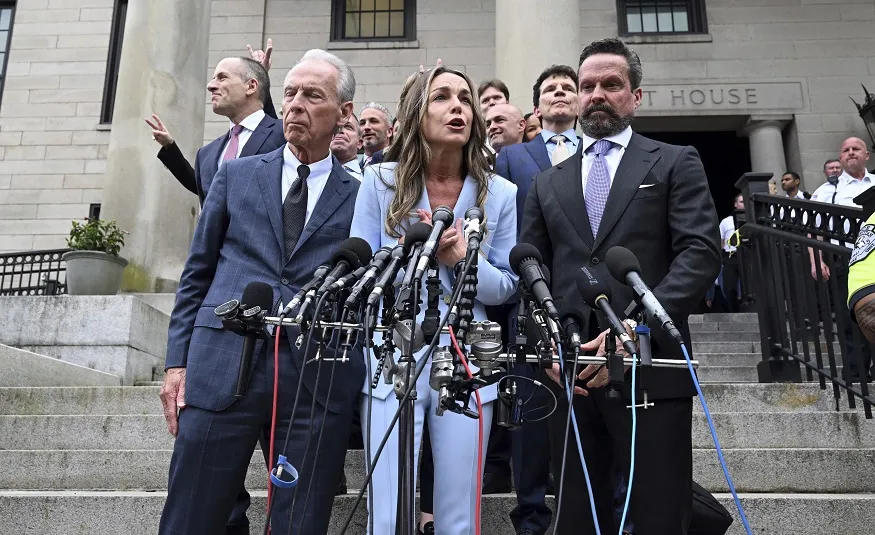

Q. Karen Read granted an inordinate number of interviews as her case was pending, including on the courthouse steps at the end of each day’s trial session. Did her lawyers get away with an error in judgment, or was this a smart strategy worth attempting to replicate with the right client?

KENDALL: It clearly worked for the Read defense. The case shifted from a trial to a tawdry reality TV show. The prosecutor carries the burden of proof, and the jurors’ expectations that the prosecutor is in control of the situation. Once the jurors conclude the government has not done its job competently, the prosecutors have fumbled the burden of proof.

MEDWED: It struck me as far too risky and somewhat bizarre because a defendant’s own words out of court are admissible as “non-hearsay.” In fact, the prosecution did seek to score some points with her admissions of excessive drinking.

I see the value of trying to humanize the defendant, but it is safer to use proxies for that, e.g., friends and family.

Q. The fact that Karen Read is an attractive white woman seems to have played into the amount of attention and resources this case received. Is that a phenomenon the legal profession can/should address, or is that more of a media issue?

DINER: In this case, which has gripped the public attention for such a long time, I think the conclusion of the trial gives us an opportunity to reflect how this case would have been different if Karen Read was not a white woman of privilege and means.

The criminal legal system is full of inequities, and the fact that the defendant in this case was able to post bail and wasn’t held in custody while the case was pending made a huge difference. Her race, class and gender all contributed to her ability to post bail and await trial in the community.

She was able to work directly with her lawyers in a way that people can’t from behind bars. She was able to give interviews and craft a public narrative that a person without means would be unable to do. All that work helped contribute to the verdict, and that is a privilege that most people charged with second-degree murder do not have.

This in no way justifies the overcharging and suspect police actions by the commonwealth. Nor is it the only explanation for the verdict. But it is an important dynamic that we as a legal community need to explore.

MEDWED: I think it’s more of a media issue and societal phenomenon than an issue for the legal profession to address. For instance, scholars have documented “missing white woman syndrome,” suggesting that the public is more fascinated by the disappearance of white women than women of color. Systemic racism has deep roots that are far too tangled, unyielding and complicated for lawyers to tackle on their own.

LU: The attractive white woman syndrome was an indispensable factor in her success. Trial lawyers will want to factor it into their preparation.

Many years ago, I was a practicing attorney. I had an administrative assistant who claimed that she could tell whether we would win the case the first time the client — male or female — entered the office. I never knew her to be wrong.

KENDALL: It is always important to have a client the jury can sympathize with. This goes beyond any specific gender or race. Jurors quickly develop a sense of the defendant and whether they like them.

Q. Hindsight is 20-20, but should the Norfolk County District Attorney’s Office have tried Karen Read a second time?

LU: Absolutely, because it would have amounted to special treatment to not retry the case. I don’t remember a case, ever, in which a hung jury was not retried at least once, homicide or not. We must not have special treatment for the privileged few.

MEDWED: Even without hindsight, this case cried out for a plea deal to OUI after the first trial. The prosecution simply had too many holes to patch up in the case that were generated by the failings of the police investigation.

Q. Was it a waste of resources to hire special prosecutor Hank Brennan? Why or why not?

LU: In the beginning, I thought so. And (ADA Adam) Lally’s excellent dry run in trial No. 1 had inestimable value to Mr. Brennan’s ability to try the bravura case he did. But, at the end of the day, based on Mr. Brennan’s stellar courtroom performance, I recant. It was a wise decision to bring Mr. Brennan on.

Justice is a process and not a result. It was important that both the defense and the commonwealth have high-level representation in this case. In addition, this case illuminates many difficult societal issues. Why add to that a disparity in the level of lawyering that might cloud these difficult issues?