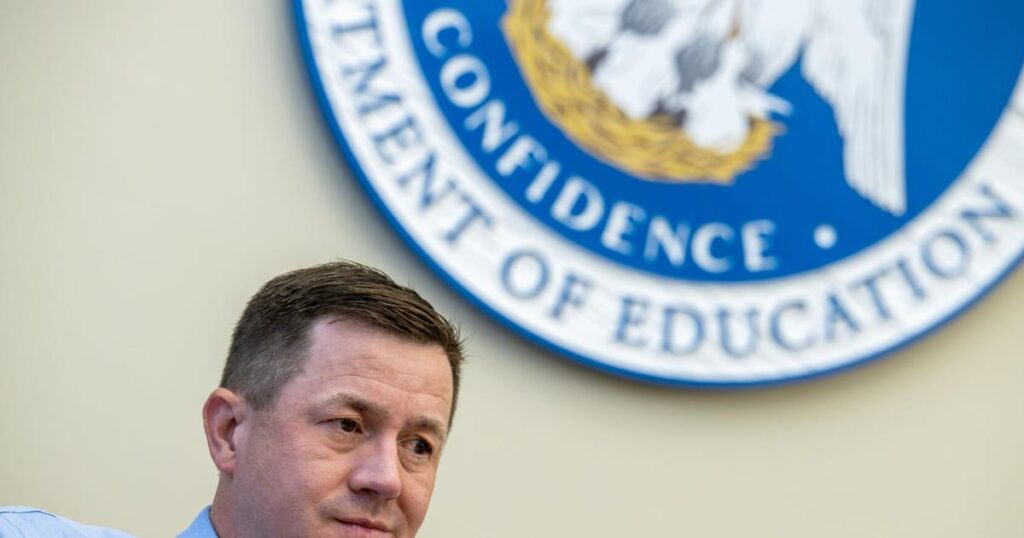

This is Cade Brumley in his element.

Louisiana’s state superintendent of education parks his Ford Expedition outside of a rural elementary school. He greets a school district official and asks about his wife, then strides into a conference room crowded with school and district administrators. He leads a lively and wide-ranging discussion on a host of education shop talk, speaking about math instruction, tutoring and teacher certification with an expert’s acumen and a communicator’s clarity.

Then Brumley, a former teacher and principal, tours a few classrooms where students use the math flashcards he had shipped to every elementary school. “This is where the magical work is happening,” he tells school staffers on his way out. “I can’t thank you enough.”

The school visit took place in early October. Several months earlier, in April, Brumley, was on a different, more public stage — the guest on a talk show hosted by Tony Perkins, head of the Family Research Council, a think tank that opposes same-sex marriage and “LGBTQ indoctrination” in schools. There, Brumley discussed the social issues roiling many states and local districts, and said schools must “reject radical ideologies.”

“Schools don’t need to be for indoctrination,” he said, adding that students should be taught to read, do math and “love their country.”

State Superintendent of Education Dr. Cade Brumley talks to students in Candace Graham’s second-grade class during a visit to French Settlement Elementary School in October.

In his five years as Louisiana’s education chief, Brumley, 44, has navigated the two overlapping — but distinct — realms of education policy and education politics he encountered in that rural school and on that political talk show. As a career educator steeped in policy, he’s driven improved student outcomes. As a public official in a conservative state, he’s demonstrated a knack for the politics around education and the ever-roiling culture wars.

Under his leadership, formerly back-of-the-pack Louisiana has shot up in national rankings, with its 4th graders leading the country in reading growth, while Brumley has notched major policy wins, including literacy reforms, a statewide tutoring program and stricter school accountability. He’s now setting out to achieve in math what he accomplished in reading.

Still, Brumley is viewed less as a partisan combatant than an amicable policy wonk and even-keeled executive, according to interviews with 20 current and former state officials, district leaders, advocates and others who have worked with or observed Brumley closely throughout his career.

He has managed to find common ground with business groups and teachers unions, Democratic and Republican governors, reformers and traditionalists.

“He’s good at working with people,” said Frederick Hess, a center-right education pundit. “He’s not an ideologue.”

Yet at times, advocates argue, Brumley’s political instincts have appeared to drive his decision-making, as when he dismantled an equity office he had established or promoted videos produced by a right-wing media company for classroom use.

“In the past few years, I think he’s allowed the political climate to impact the type of leader he is,” said Tramelle Howard, Louisiana state director of Education Trust, a left-leaning advocacy group.

Despite the impressive academic gains, Brumley has acknowledged that student scores remain low, absenteeism is high, racial gaps are stubbornly wide and a slate of math reforms are just getting started. The question before him is whether he can tackle those challenges and push Louisiana schools to the next level while navigating the job’s political currents.

“My role is one that lives in state and national politics,” said Brumley. “My job is to get better outcomes for kids.”

An education leader who ‘got it done’

Before that October school visit, Brumley began his day in the usual way — on his knees, praying for the state’s students. Then he hopped in his SUV, radio tuned to a station playing Billy Graham sermons, and headed to the Louisiana Department of Education’s Baton Rouge offices.

A six-time marathon runner, he climbed the stairs to his fifth-floor office overlooking the state Capitol. He fielded a call from Gov. Jeff Landry about a truancy program, met with state higher education officials, then checked in with his math, literacy, attendance and artificial intelligence leadership teams. Leaning forward in his chair, red pen in hand as he posed clarifying questions, he called to mind a school principal.

“What are you struggling with right now?” he asked a deputy who oversees AI work. “Is there anything you need from me?”

Brumley listens to Adam DiBenedetto, the state education department’s director of innovation, during a monthly check-in meeting.

Brumley grew up in Converse, a village of about 400 residents an hour south of Shreveport, the son of a school cafeteria worker and a police officer. School was the vehicle for his ambition.

“I come from a very humble family,” he said. “I was very aware that education was my ticket to the middle class.”

After college, he returned to Converse High School as a social studies teacher and coach. Under his leadership, the girls’ basketball team made it to the state playoffs for the first time in over a decade.

“He came in and turned the program around,” said Emily Anderson, 35, who was on the team. “Because he was so motivated and driven, it helped us find that in ourselves.”

Brumley rose quickly from the classroom to district leadership. In 2012, he became superintendent of DeSoto Parish, a small district of nine schools and about 5,000 students with a budget crisis so severe it was on the verge of not making payroll. Brumley had to cut costs, and created a plan that included layoffs and school closures. When he presented it at a school board meeting, local law enforcement insisted he wear a bulletproof vest.

He weathered the storm, partly by cultivating relationships in the parish’s Black community. By the time he left, graduation rates were up, suspensions were down and the district had earned its first-ever A state rating.

“He was not a loud or a flashy kind of a guy at all,” said Dudley Glenn, a longtime DeSoto school board member, “but he got it done.”

In 2018, Brumley took the top job in Jefferson Parish, whose enrollment is 10 times the size of DeSoto’s. There he led a successful campaign to boost teacher pay through a tax hike by rallying business and teachers union leaders behind the cause.

When state Superintendent of Education John White stepped down in 2020 after eight years in the role, the state Board of Education decided, after two inconclusive rounds of voting, to give Brumley the job.

Critics had cast him as a champion of the education establishment, but he soon defied those expectations. He pushed for looser COVID restrictions and stricter school accountability, putting him at odds with teachers unions, superintendents and then-Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat who had celebrated Brumley’s selection.

Then he scored a major victory — a literacy campaign that earned national praise and is credited with helping raise students’ reading scores. Working with lawmakers, he developed a package of bills rooted in research-based practices known as the “science of reading.” He teamed up with an advocacy group to establish a statewide tutoring program for struggling readers, which he helped convince the Legislature to fund. And his agency provided schools with on-the-ground support to effectively enact the changes.

“You’re partnering with the people closest to the work versus just giving policy directives,” said St. Charles Parish Schools Superintendent Ken Oertling, adding that such support was “lacking under previous superintendents.”

Brumley said he and Gov. Jeff Landry, left, are “very aligned” in their beliefs.

When Landry, a Trump-aligned Republican, ran for governor in 2023, Brumley said he secured his blessing: “He was like, ‘Cade, if I win man, I’m going to support you.’” It was a shrewd political move, since the governor appoints three of the 11 board of education members, but it also reflected their shared views.

“Philosophically, we’re very aligned on basic issues,” Brumley said.

Landry introduced LA GATOR, a private school voucher program like those embraced by Trump and many Republican-led states. Public school supporters fiercely opposed the program, but Brumley championed it, saying that giving parents tax dollars to pay for private school tuition advances “educational freedom.”

While many public school educators were upset, Brumley also advocated for teacher raises and attributed academic gains to their hard work.

“There have been a whole lot of really tough conversations,” said Rapides Parish Schools Superintendent Jeff Powell. “But at the end of the day, we’re moving forward under his leadership.”

Wading into the culture wars

Brumley often pursues a nonpartisan agenda, like literacy reform, that he knows works for students. But at times politics take center stage.

After he was appointed state superintendent in May 2020, just as anti-racism protests erupted across the U.S., he established an Office of Equity, Inclusion and Opportunities within the state education department and hired Kelli Peterson, a New Orleans school official, to run it. His agency also announced a partnership with LSU to train school leaders in social-emotional learning, including “SEL through a racial equity lens,” partly to help reduce student suspensions.

But as equity programs nationwide faced a conservative backlash, Brumley dissolved the office and discontinued the training. In July 2021, Peterson addressed a scathing resignation letter to Brumley.

“I choose to no longer serve in an organization that allows political agendas to drive decisions,” she wrote.

When announcing the SEL staff training, Brumley had said that supporting students’ social-emotional health “leads to greater academic outcomes and happier kids.” But a year later, he objected to new early learning standards because they referenced social-emotional learning, which he now suggested could be “a Trojan horse for critical race theory.” One of the early education experts who developed the standards called that misinformation, adding that “the department leadership knows that.”

Brumley argued in an interview that he has been consistent in pursuing academic excellence and equal opportunities for all students. He said he abandoned terms like equity and social-emotional learning after others twisted their meaning.

“In so many ways, words got hijacked,” he said, “they got radicalized.”

U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon talks with Cade Brumley, Louisiana Superintendent of Education, while touring the Jefferson Terrace Academy on Monday, August 11, 2025 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

He’s made other forays into politics. He has spoken at events hosted by Moms for Liberty and the Heritage Foundation, two conservative advocacy groups. He advised schools not to comply with former President Biden’s rules extending Title IX anti-discrimination protections to LGBTQ+ students and he welcomed the use of videos by the right-wing nonprofit PragerU, including one in which an animated Christopher Columbus downplays the horrors of slavery.

Brumley said his political stances, such as his opposition to Biden’s Title IX rules, reflect his genuine beliefs — “I don’t think that biological males should be in the girls’ bathroom” — and what he thinks is best for students, like reopening schools post-COVID. But he said politics isn’t his main concern.

“I don’t spend my day focused on culture issues,” he said. “I spend my day focused on there aren’t enough kids that can read on grade level, there aren’t enough that can do math.”

Thinking about the future

Brumley’s stock keeps rising.

U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon recently kicked off a cross-country school tour in Louisiana where she called Brumley “a good resource and a good friend,” and Landry tapped him to lead a new higher-education task force. All the buzz has fueled speculation about his next moves, including whether he would apply to be LSU’s next president.

“I had people talking to me about that, but I didn’t do it,” Brumley said. “I routinely have opportunities presented to do other things, but I haven’t felt the desire to do any of that yet.”

State Superintendent of Education Cade Brumley talks to fourth-grade students in Sheli Harris’ class during a visit to French Settlement Elementary School on Monday, October 6, 2025.

For now, Brumley appears to be enjoying his job. During his early October visit to French Settlement Elementary School, he observed a fourth-grade classroom where pairs of students were competing to see who could solve multiplication flashcards first.

Brumley asked the students whether they find math easy or hard. One girl said it’s easy because her mom is a math teacher: “I think you have an unfair advantage!” Brumley joked. Then he asked the students to consider what they want to do when they’re older, urging them to choose jobs they’ll love.

Later, Brumley recalled how he had declared in the first grade that he wanted to become a school principal.

“I’ve been able to live out that dream,” he said, “and use the pulpit I have to get better outcomes for kids.”