Illustration: María Jesús Contreras

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

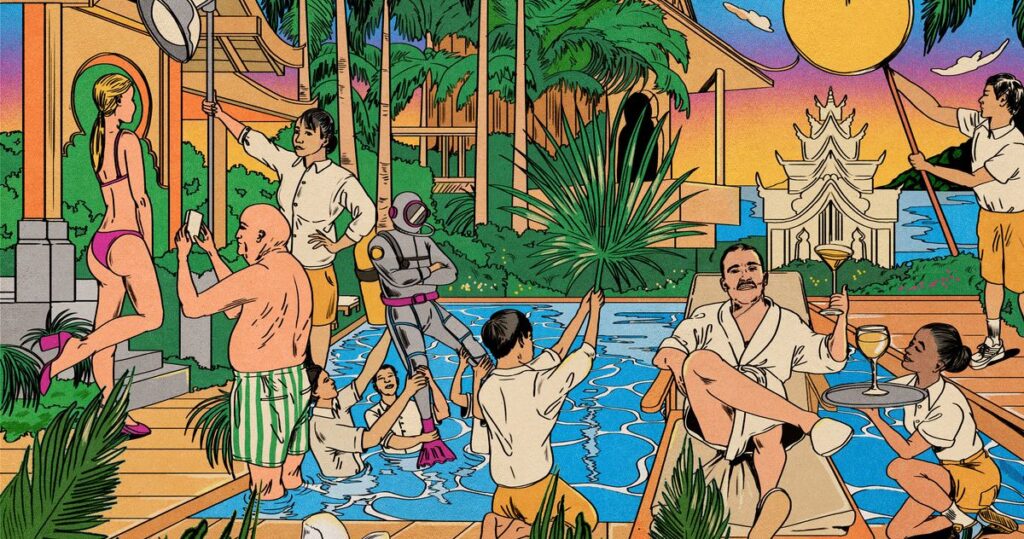

At the Four Seasons Koh Samui, a five-star hotel overlooking the Gulf of Thailand, staff study guests like spies watching their marks. Their research goes beyond the usual notes on allergies and coffee orders. “I know everything,” says Hannes Schneider, the hotel’s handsome, six-foot-six Austrian resort manager. “I know when you arrive, what kind of car you have. I have a picture of you. I know if you’ve stayed at other Four Seasons. If I call up my buddy, I know what you’ve done on a daily basis, good and bad.” Schneider, like the rest of the hotel’s management team, wears breezy linen and a stack of energy-stone bracelets, a relaxed, island-y look at odds with his management style, which he calls “relentless.” His employees — an interconnected web of bellboys, cleaners, waitstaff, supervisors — are in constant communication about guest movements to anticipate their needs or simply to greet them by name (“guest-name use is key”). “You are on permanent surveillance,” says Schneider, fixing me with his unwavering, ice-blue stare. “Whatever you say, whatever you do will be observed. And judged.”

The hotel, on the Thai resort island of Koh Samui, is the setting of the third season of The White Lotus, the social satire from writer-director Mike White. Previous seasons have also filmed at Four Seasons, an upscale hotel chain famous for serving guests “hand and foot,” as one former visitor put it. And the brand does feel like a suitable partner for the show, which features privileged travelers terrorizing hotel staff and fellow tourists with their grotesque, spoiled behavior.

HBO bought out the entire resort for two months in early 2024. White spent most of the previous year in Thailand scouting locations, studying Thai culture, and observing the kinds of tourists that come to the country; initially, he was reluctant to film on Koh Samui because he’d been eliminated from The Amazing Race there. “He had this very negative-feeling spiritually about Koh Samui,” says David Bernad, the show’s producer. Then, while in Chiang Mai, he was hospitalized with bronchitis and given a nebulizer. “He took the nebulizer, and he hallucinated,” explains Bernad. He visualized all of season three in a drugged haze. “Thailand is a witchy place,” he adds. White’s visions produced a fresh handful of twisted relationships: a trio of longtime girlfriends who obviously hate each other; the Ratliffs, a moneyed southern family indulging their daughter’s interest in Buddhism; and two couples — flighty young women paired with middle-aged boyfriends who spend most of the season scowling and drinking.

When I stayed at the Four Seasons in January, there were indeed a number of geriatric men who spent much of their time couched in the sun, snapping photos of their youthful, bikini-clad girlfriends in the infinity pool. I also clocked a handful of tech-bro types (ragged gym clothes, wired headphones, green juice for breakfast — foregoing the doughnut bar and caviar bucket). Most guests were white, except for the nannies, of whom there seemed to be one per child. “A vacation for 50-, 60-, 70-thousand dollars is normal for them,” says Schneider of his guests. During peak season, rates for the hotel’s most basic villa begin around $2,200 a night; it also manages ten privately owned residences, which can be rented for up to $30,000 a night and come with live-in butlers. “You’re dealing with people who have everything in life,” Schneider says. “Everything is handed to them on a silver platter.” They are business tycoons, celebrities, jet-setters — as in, they travel exclusively on jets. Sometimes, so many jets arrive with people bound for this resort they clog up the island’s only airport. (The week I was there, one was simply “too big to land somewhere,” says Schneider, who had to arrange a smaller backup.) Visitors come chiefly from the U.S., Central Europe, and the Persian Gulf, which differs from the rest of the country, where the majority of tourists are from China, Malaysia, and India.

“Thailand was asleep for a long time,” says Schneider, of the pandemic’s effect on the country’s tourism industry, which is one of its main economic sectors. Just last year tourism began to approach pre-pandemic numbers, and the country is anticipating an influx of visitors thanks to The White Lotus, which boosted tourism in Maui and Sicily, the sites of previous seasons. All of the Thai workers I spoke with came from the mainland and had done stints at Koh Samui’s other luxury resorts — Banyan Tree, InterContinental, the W. They live in housing nearby, which Four Seasons pays for, motorbike to work, and take their meals in the staff canteen. They described the Four Seasons clientele as older and more refined than at other hotels in the area. At the W, for example, the guests are younger and wilder: “You don’t get to rest, it’s a party all the time,” says one spa worker, named Tipfy (she goes by a nickname, like her colleagues — Banana, Arm, Film, to name a few. “It’s usually a random noun or thing that has absolutely nothing to do with their actual name,” explained a Thai friend of mine. “You’ll come across people named Book, Plate, Shoe”). Guest-facing workers — at the bar, restaurants, or spa — must speak some English (the hotel provides online classes) and their work does involve a lot of enthusiastic listening; I saw one poolside worker treated to a 30-minute monologue from a young mom about her newborn’s bowel movements. When I asked Tipfy and her colleague, Piano, if they often deal with moody guests, they nod and laugh. “In the spa, people have physical and emotional issues,” says Fan Mekloy, the spa director. How do they handle ultrastressed guests? “Keep calm all the time,” says Tipfy, shrugging. “Just smile. Be calm. Say okay. ‘Okay, madam. Okay, sir.’”

Photo: Four Seasons Resort Koh Samui

Many of the non-Thai staff insist that a certain agreeableness is natural to Thai culture, a by-product of Buddhism. Jasjit “J.J.” Singh Assi, the hotel’s general manager, says that while staff do discuss obnoxious guests, it’s nowhere near as sensational as the show suggests: “There is a bit of exaggeration there. We don’t go into guest rooms, and we don’t shit in their suitcases.” If a guest gets angry at his Thai staff, they are told to call Assi or Schneider, who will take over. “It is not in their nature to be aggressive,” says Assi. “If you show aggression to them, they will go into a cocoon.”

Still, being outwardly agreeable due to cultural norms isn’t the same as actually being relaxed, especially in a hotel where guests “want service like this,” says Assi, snapping his fingers. Like his colleague, he cultivates a laid-back attitude that conceals an assertive, unyielding leadership style (he hails from three generations of Indian military generals, and his grandfather helped found the Royal Indian Air Force). Assi’s approach is more soft power — when we meet over breakfast, he speaks to me in Punjabi, says I look like his sister, and orders his Indian chef to make me dishes from my childhood. He says I can ask for anything I want and he’ll do his best to make it happen, and not just with food. “We can arrange virtually anything” is a line you’ll find all over the resort’s website, next to a phone number. It seems to be the hotel’s mantra, and is a point of pride for everyone I speak to.

It’s almost like the more outrageous the request, the more juiced Assi and his crew are to fulfill it — to prove they can make the impossible happen. Once a guest demanded, and received, a magician; the hotel has the island’s only English-speaking Buddhist monk on speed dial; recently, a guest arrived at the hotel at 10 p.m. and wanted to propose to his girlfriend right away. “He says, ‘I need to buy an expensive ring right now,’” recalls Assi, who flew in a jeweler from Bangkok, since everything on the island was closed. While the guest chose a ring, hotel staff brought his girlfriend to the beach, where a private dinner waited. The proposal took place at midnight. Schneider once welcomed a famous singer with a working gramophone made of sugar. “Everybody does a big chocolate block,” he says, disdainfully. “So passé. How can you really woo them?” Those enrolled in the hotel’s elite tier (an invitation-only, annual membership program) receive napkins and pillowcases embroidered with their initials — “It’s pretty insane,” he says.

Schneider qualifies that exorbitant requests are fulfilled only after the hotel confirms the guest can pay for it by reviewing their financial documents: “They all have their P&Ls, obviously.” Still, “regular” guests receive an unusual level of service. One told me she was shocked when she noticed housekeeping had carefully cleaned her hairbrush, removing all of the hair. “I didn’t have to use my brain,” says a guest who honeymooned at the hotel last summer. One evening at dinner, a man rushed past me holding a child who threw up midair, splashing vomit on my shoes. Within seconds the staff had swept me to a new table, offering Champagne, napkins, heartfelt apologies. The vomit vanished as if by magic, and the offending child was whisked to the beach.

Schneider encourages guests to leave and explore the island — “what’s real in Thailand,” as he puts it — but emphasizes that they never do. “They all come back right away,” he adds, with some satisfaction. “What we would like to do is bring Thailand into the hotel.” Which means: Thai food, Thai boxing, and Thai-inspired wellness offerings — gong baths, massage, and Buddhist chanting, which I attended one day, that did fill me with a mystical sense of well-being, until that kid threw up on me.

Muay Thai instructor Aan Deesamer (right) boxes with a guest.

Photo: Sangeeta Singh-Kurtz

The resort has an endless menu of recreation, from yachting to Reiki healing, but Muay Thai boxing is its most popular activity. This is largely because of its instructor, Aan Deesamer. He is ripped and tattooed, with a silver chain and matching tooth “for extra come and get me.” He’s from Liverpool, and his accent completes the impression that you’re scrapping with a Guy Ritchie character. He torments me the entire class; when I tell him I’m tired, he laughs. “Do you think I care if you’re tired? Hit me. Make me feel pain.” When I nail him in the stomach, he actually rolls his eyes. Why do guests pay $73 to get negged for 60 minutes? “We don’t get spoiled here,” he says. “The guests are just normal human beings.”

To cosplay authenticity in the lap of luxury — to be given the “real” experience, even if that means getting punched in the face — seems to be the point. Guests will sometimes antagonize Deesamer, really try to fight him. Some people, big men, usually, will get aggressive, attempt to lift him off the ground, body slam him. Once he knocked out a belligerent American. “I got behind him to make a choke. ‘Okay,’ I said. ‘Please, tap if you feel yourself going to sleep. Shouldn’t take longer than ten seconds.’ He was too stubborn to tap. I let go. He collapsed to the ground. His daughter screamed, ‘You killed my dad!’ I said, ‘No, no. He’s taking a rest.’ He woke up, said, ‘What happened to me?’ I said: ‘I just put you to sleep.’”

He doesn’t often “humble” guests, but sometimes it feels like part of the job. “Especially with rich men. Because they’re powerful in their world and have so much money. But this is my world now.” He trained several actors from The White Lotus, including Arnas Fedaravičius, who plays a hot private butler and health coach, and Patrick Schwarzenegger, the bratty, horny, eldest Ratliff brother. “He was on his phone, on his watch. I stood and waited for him for five minutes,” says Deesamer. Before they started boxing, he says, Schwarzenegger began to complain about sore shoulders. “So I ask him to explain to me the problem. He says, ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter.’ Just showed me no respect at all. I know who he is, you know what I mean? But come on, you’re in my home.” (Bernad, the show’s producer, later tells me that The White Lotus actors can morph into their characters throughout filming. “Whether we cast really well, or we cast people who are like their characters, everything starts to blend.”)

While Deesamer and the other workers — sound healers, meditation gurus, dancers — offer guests an approximation of Thai culture, the resort’s small army of groundskeepers are fighting to maintain another mirage: the hotel’s 43-acre property, which tumbles down from two verdant mountains toward the sea in a manicured jungle. Forty or so workers rise at the crack of dawn to fight an endless battle with nature. I found the property curiously devoid of the creepy crawlies — the lizards, bugs, and occasional water monitors I’ve encountered at pretty much every other hotel in Southeast Asia. I later learned there’s a twice-weekly mosquito purging, where each building is smoked out with a mysterious chemical to destroy bugs. The hotel recently rebuilt the beach, shipping in tons of sand after winter storms. One morning, I watched a man shimmy up a 100-foot coconut tree (the resort is built among nearly 900) to pluck a single frond.

Guests still complain about the elements, as if the Four Seasons could control them, too. “‘The water’s too salty.’ ‘The sun’s too sunny,’” says Zoe Thomas, who works for Koh Samui’s local dive center, Discovery Divers, and runs the hotel’s scuba and snorkeling program. Occasionally, she has to stop guests from plucking live animals — sea slugs, cowries, corals — from the sensitive reef that protects the beach. One worker, whose job it is to ask for guests’ feedback at the end of their stay, says they often gripe about the temperature of the pool but are sometimes upset about the weather more generally — “sometimes they’ll ask us to bring the sun,” he says, with an exasperated wave at the sky.

Of course, some demands are impossible to fulfill, but the goal is to give visitors the feeling of being cared for. Acknowledging their desires seems to be more important than actually sending the monks, magicians, and pastry gramophones. “What everybody wants is recognition,” says one manager. For instance, Thomas often deals with guests who insist on scuba diving, even though they can’t swim and are terrified of the water. If they get through skills training, instructors will hold onto them throughout the entire dive. And if they don’t, “We take ’em and we dunk ’em at one meter, basically, and let ’em feel like they’re having an experience.” The ultrarich “need to be handheld,” says a manager, but “we can never tell a guest what they want,” says another. “It’s a matter of listening to them. Then finding a solution for them, but more give them the illusion of choice. In the end, the guest still believes he makes a decision.”

I ask the managers if they ever draw lines with requests. Schnieder says the hotel won’t buy you weed, but they’ll tell you where to get it. (Cannabis is decriminalized in Thailand, and the moment you leave Samui’s airport, you hit a main road lined with storefronts selling it.) Assi says he doesn’t allow sex workers into the hotel, but if a guest insists on bringing “in a partner they pick up from somewhere,” they must register them. (Prostitution is illegal in Thailand, but the Thai sex industry is thriving, largely due to the internet, according to Ronald Weitzer, a criminology professor who has written a book on the subject: “There are several online, membership-only discussion forums where current and former sex tourists and expats — who call themselves ‘sexpats’ — like to discuss and recommend various bars, massage parlors, brothels.”)

However, if a guest is renting one of the residences — which are managed by the hotel but not subject to its rules — they can do whatever they want. And sometimes they do: In 2021 a British crypto trader took crystal meth, commandeered a speedboat, and began shooting pistol rounds toward Four Seasons, where he was staying. It wasn’t the first time something White Lotus–y happened on Koh Samui: In 2015, two men were put to death for raping and killing British backpackers. A recent Samui trial resulted in a life prison sentence for a man who was found guilty of murdering and dismembering his lover. Last summer, a local housekeeper inherited a few million dollars and some cats from her French madam, who shot herself on her Samui property. Bernad says that none of these events inspired the season, but the hotel seems to be a character in its own right. “It’s like a Disneyland for rich bohemians from Malibu,” gripes the Buddhist-curious Ratliff daughter, describing The White Lotus–ified version of the Four Seasons. When I ask Assi if he lives on resort, he laughs. “No, no, no, I refused. A guy like me will go crazy here, man.”

Sign Up for The White Lotus Club

Watch, dissect, discuss, and obsess about season three with New York writers and editors.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice

See All